How to assess your corporate treasury and risk management in the SVB aftermath

- Decrease your deposit exposure and diversify

- Assess the stability of your financial counterparties and banks

- How should you invest your corporate treasury going forward?

The past week has been incredible. A major bank failure has not occurred in the U.S. since the great financial crisis in 2009. Many risk managers, finance teams, and founders are going through this for the first time. I’d like to offer some advice on how finance teams can enhance their risk management and corporate treasury strategy to prevent future disruption. Every company’s individual circumstances are different, so please do not take this as gospel but rather as a rough guideline to think about your capital allocation strategy.

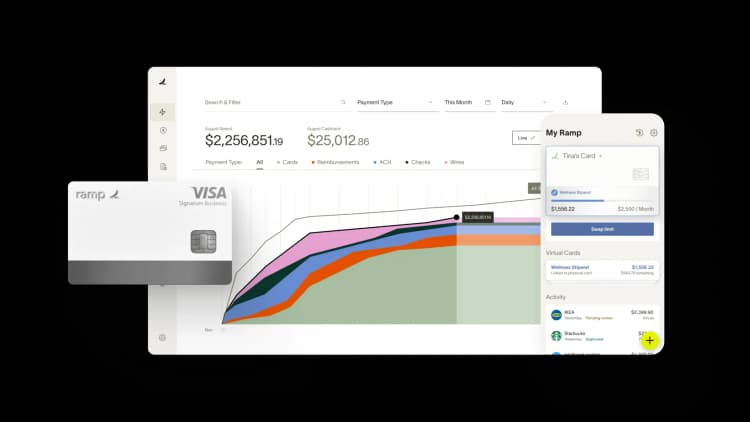

Risk and corporate treasury are two things that are paramount to the Finance team here at Ramp. The biggest reason is simply that we have a lot of capital: we’ve raised significant capital in the past several years, we currently manage a liability stack of several hundred million dollars of warehouse financing, and we process $10 billion of one-way payments (much more if you count round-trip payments). As a payments business, it’s imperative that we don’t suffer from any operational or banking failures.

Here are some of our best practices to make sure that we have a robust Treasury setup.

Decrease your deposit exposure and diversify

For the past several quarters, Ramp consistently had a low single-digit percent of its corporate treasury in the form of banking deposits. This low dollar amount was spread out among at least three or four different banking institutions at all times. We did this so as to decrease idiosyncratic banking and payment rail failures (the latter of which does come up from time to time). We wanted to make sure that if a particular payment rail or bank experienced a service interruption, that we would have robust backups in place.

More importantly though is the fact that we made a conscious decision to keep most of our Corporate Treasury out of cash deposits, and instead we invested it in a number of financial instruments across multiple counterparties: money market funds, T-bills, investment grade corporate bonds with laddered maturities, and a small amount of ETFs and mutual funds. This made it so that Ramp itself was not greatly exposed to any individual bank, asset class, or financial institution. We diversified our investments not only through sector and asset selection, but also through time: our investments had a diverse maturity and duration profile and we had natural principal repayments on these investments over time.

Assess the stability of your financial counterparties and banks

A lot of founders and entrepreneurs are probably thinking about whether it’s safe for them to bank with XYZ. How should you evaluate your financial counterparties?

First, banks in America are extremely safe. They tend not to go under. They are very, very well-regulated entities, particularly since the Great Finance Crisis. Thanks to federal regulations put in place over the last decade or two, banks in the US generally carry more equity reserves, and are much less levered than they were in the early 2000s. That is not to say that they’re completely devoid of risk, as we saw this past week.

Also, not all banks are created equal. Banks’ stability varies based in part on:

- Their tangible net assets

- The nature of their assets—how fragile is the valuation?

- The nature of their liabilities—how sticky is the depositor base? What is the concentration of their customer base? How much of it is insured vs uninsured?

- The amount of interest rate risk or credit risk that a bank has taken on

- The liability stack, or leverage ratio, of the bank

For entrepreneurs who may not know the ins-and-outs of each bank’s capital ratios, capital structures, cap tables, and what not, the best thing to do is really just diversification as a way to hedge counterparty risk. It makes sense to have at least two or three providers that will provide you similar—maybe even redundant—services, so that you're not entirely beholden to a single vendor. This includes deposits, investments, term loans, lines of credit, letters of credit, and other forms of borrowing.

You also want to make sure you have some protections around committed as opposed to uncommitted financing, as well as considerations of ROFRs or exclusivity clauses. Over the past 3-4 years, Ramp has set up more than seven active banking relationships covering some of these functionalities. If anything, this number will likely increase over time.

How should you invest your corporate treasury going forward?

First, you should anchor the discussion: how much runway do you have based on your current or projected cash burn, and how much liquidity do you need? Specifically, think about how much liquidity you need in the short term (weeks), medium term (months or quarter), and long term (years). Answering some of those questions will help you think about strategic asset allocations. This will depend on your budget and financial projections.

In an ideal scenario, your company has enough cash and cash equivalents in the Corporate Treasury for two or three years of runway. Given that, it should be made up of a few different buckets:

- Capital that you can tap into on a day-to-day, week-by-week basis to meet your current operating needs. This could be allocated either into cash, or principal protected money market funds.

- Investments that you plan to tap into in a few months. This could be short dated T-bills or Corporate Bonds.

- Investments that you won't tap into for potentially a year or two down the line. This could be slightly longer duration T-bills or Corporate Bonds.

How much capital you need for each of these buckets should inform how you should be investing.

A few other somewhat technical things to keep in mind:

- Day-to-day capital has to be easily accessible and diverse. A lot of people just put them into money market funds or sweep accounts. These instruments are the most accessible and settle on a T+0 basis (aka on a spot basis). That means you could literally liquidate your investments, and wire money out same-day. Another option is T-bills which can be traded in and out very quickly on a T+1 basis. This means if you sell a bond today, the cash is in your bank account by tomorrow ready to be wired.

- In contrast, most stocks and corporate bonds trade on a T+2 basis. What this means is if you buy and sell these bonds today, you won't have the ability to access their true liquidity (aka cash) for two business days. If you're in a true banking crisis or liquidity crunch and you require contemporaneous financing, you likely should not depend on your corporate bonds or equity investments to solve your issues. You should be tapping into your money market funds and/or your T-bills because that cash shows up very fast. Again, the nuances between T+0, T+1, and T+2 trade settlement basically never comes up under normal circumstances. But in crises, could be paramount to understand so that you understand which pockets of capital to dip into.

On a closely related note: I know that we’ve mostly been talking about the asset side of the Corporate Treasury, but on the liability side of the house, if you’re negotiating lines of credits and revolvers, be sure to absolutely understand how quickly your lenders can fund. In our experience, we’ve found that almost no lender will fund on a T+0 basis. Some lenders are willing to fund on T+1 basis, which is great because that means you get next-day funding, comparable to selling T-bills. Lastly, most lenders will definitely fund on T+2 or T+3 basis. Under normal scenarios, this distinction generally doesn’t come up for companies, but if you're in a liquidity crunch, this is not the ideal scenario. When you are negotiating loan agreements, make sure you understand your funding mechanics!

We will share more thoughts in the future on how to negotiate / re-negotiate your lines of credit in the new funding environment, as well as simple strategies for hedging interest rate risk from your balance sheet.

“In the public sector, every hour and every dollar belongs to the taxpayer. We can't afford to waste either. Ramp ensures we don't.”

Carly Ching

Finance Specialist, City of Ketchum

“Compared to our previous vendor, Ramp gave us true transaction-level granularity, making it possible for me to audit thousands of transactions in record time.”

Lisa Norris

Director of Compliance & Privacy Officer, ABB Optical

“Ramp gives us one structured intake, one set of guardrails, and clean data end‑to‑end— that’s how we save 20 hours/month and buy back days at close.”

David Eckstein

CFO, Vanta

“Ramp is the only vendor that can service all of our employees across the globe in one unified system. They handle multiple currencies seamlessly, integrate with all of our accounting systems, and thanks to their customizable card and policy controls, we're compliant worldwide. ”

Brandon Zell

Chief Accounting Officer, Notion

“When our teams need something, they usually need it right away. The more time we can save doing all those tedious tasks, the more time we can dedicate to supporting our student-athletes.”

Sarah Harris

Secretary, The University of Tennessee Athletics Foundation, Inc.

“Ramp had everything we were looking for, and even things we weren't looking for. The policy aspects, that's something I never even dreamed of that a purchasing card program could handle.”

Doug Volesky

Director of Finance, City of Mount Vernon

“Switching from Brex to Ramp wasn't just a platform swap—it was a strategic upgrade that aligned with our mission to be agile, efficient, and financially savvy.”

Lily Liu

CEO, Piñata

“With Ramp, everything lives in one place. You can click into a vendor and see every transaction, invoice, and contract. That didn't exist in Zip. It's made approvals much faster because decision-makers aren't chasing down information—they have it all at their fingertips.”

Ryan Williams

Manager, Contract and Vendor Management, Advisor360°