- Types of inventory

- Inventory accounting

- Absorption vs. variable costing

- Inventory valuation methods

- Other inventory accounting considerations

- The importance of inventory

- Track inventory costs automatically with Ramp's real-time spend visibility

Inventory is the heartbeat of many successful retail businesses. It’s the connection between many moving parts, including manufacturing, business strategy, pricing, and customer satisfaction. Without inventory, some companies simply wouldn’t have customers.

In this article, we’ll take a look at the different types of inventory, different ways it can be recorded, and special considerations to make when accounting for inventory.

Types of inventory

For some companies that make their own goods, inventory isn’t always finished products. Many companies carry raw materials on their balance sheets (raw materials inventory). Raw materials are the basic components that are transformed into finished goods. A company technically owns inventory if it owns metals, plastics, textiles, or chemicals that'll eventually be transformed into a final product.

As raw materials undergo transformation, they enter the work-in-progress (WIP inventory) stage. This stage involves converting raw materials into intermediate goods by putting them through a specific manufacturing process. At this stage, different teams may need to coordinate across manufacturing stages (think of an assembly line). It’s also important to keep in mind that, similar to raw materials, partially completed works-in-progress still count as inventory.

The culmination of the manufacturing process happens when finished goods are ready to be sold (finished goods inventory). This type of inventory is the end product that's undergone all necessary manufacturing steps and quality checks. Finished goods are sometimes stored in warehouses before being shipped to distributors, retailers, or directly to consumers. This is the type of inventory most people think of: pre-packaged, final goods that are ready to be used.

Effective accounting of each type of inventory—raw materials, work-in-progress, and finished goods—is so important for maintaining a well-functioning and responsive inventory system. It’s important to account for each type, as companies rely on data for each type to make decisions. For example, accounting for raw materials lets management know when resources are getting low and it’s time to order more. Alternatively, tracking work-in-progress balances may help identify bottlenecks in an elaborate manufacturing process. Whatever the case, it’s important to value each type of inventory, and there are a number of journal entries that help make that happen.

Here's a comprehensive list of some other types of inventory:

- MRO (maintenance, repair, and operations) Inventory: This category includes supplies used in production but not part of the final product, such as cleaning supplies, safety gear, and repair tools.

- Transit inventory: Also known as 'in-transit inventory,' it refers to items currently being transported between locations. This is common in businesses with distributed supply chains.

- Buffer inventory: Also known as 'safety stock,' buffer inventory is extra stock held to prevent stockouts caused by delays in delivery or unexpected spikes in demand.

- Decoupling inventory: These are stocks held to separate dependencies between different stages of the production process, allowing one stage to operate independently of others.

- Cycle inventory: This is the inventory a company plans to sell in a typical buying cycle, often influenced by bulk purchasing to save costs.

- Anticipation inventory: This type involves stockpiling goods in anticipation of a spike in demand, such as seasonal items or products for a promotional event.

- Obsolete inventory: These are items that are no longer sellable due to being out of date, out of style, or surpassed by newer models.

- Consignment inventory: This inventory is in the possession of the retailer but remains the property of the supplier until sold.

- Service inventory: For service-based industries, this refers to the capacity to deliver services, like available hours of work or seats in a restaurant.

- Theoretical inventory: This is a calculated inventory level based on ideal conditions, often used for comparison with actual inventory to identify discrepancies.

Inventory accounting

Now that we’ve looked at the types of inventory, let’s look at the types of journal entries you’ll see when accounting for inventory. If a company just buys its inventory, it may or may not use some of these entries.

As mentioned earlier, manufacturing involves multiple steps, including the purchase of raw materials, conversion of raw materials into WIP, and the ultimate creation of finished goods. When a company buys raw materials, they're usually captured on the balance sheet, not as an expense.

- DR Raw Materials Inventory

- CR Cash (or Accounts Payable if purchased on credit)

As raw materials are used, that inventory balance is reduced to reflect an increase in WIP.

- DR Work In Progress

- CR Raw Materials Inventory

As WIP is completed, final inventory is recognized.

- DR Inventory (or Finished Goods Inventory)

- CR Work in Progress

If a company simply buys inventory for sale, it will also recognize inventory like above. However, it will credit the payment method used to capture the goods.

- DR Inventory

- CR Cash (or Accounts payable if purchased on credit)

Two entries are made when a company sells inventory. First, it has to get rid of the inventory on its books and recognize that inventory as an expense called “cost of goods sold”. Second, it has to recognize the revenue portion of the transaction. Note that the profit the company has earned is captured in this entry as the difference between the inventory’s cost and what it was sold for.

- DR Cost of Goods Sold ($XXX)

- CR Inventory (or Finished Goods Inventory) ($XXX)

- DR Cash (or Accounts Receivable for credit sales) ($YYY)

- CR Revenue ($YYY)

These entries provide a simplified overview, and actual journal entries can be more complex depending on factors like discounts, returns, or niche accounting methods used by a specific industry.

Absorption vs. variable costing

Now that we’ve talked through some inventory-related journal entries, let’s look at the dollars behind the entries. How exactly do you determine the cost that goes into that inventory? There are several methods, each with their own advantages and disadvantages.

One method is called absorption costing. Absorption costing is a method of allocating all manufacturing costs, both variable and fixed, to the cost of a product. This approach considers direct costs such as direct materials and direct labor, as well as indirect costs like factory overhead. The key feature of absorption costing is that it absorbs fixed manufacturing overhead costs into the cost of each unit produced.

The other method is called variable costing. Variable costing considers only the variable manufacturing costs (direct materials, direct labor, and variable overhead) as the cost of a product. Fixed manufacturing overhead costs are treated as period costs and expensed when incurred.

Which one should a company choose? If a company is preparing external reports, it usually has to do absorption costing. Variable costing is particularly useful for internal management purposes as it provides a clearer picture of how costs behave with changes in production levels. However, it’s not allowed under generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). Also, keep in mind that variable costing may produce less net income in the short term (since it expenses more upfront), but both methods should end up yielding the same total revenue, expenses, and net income over a long enough timeline.

Inventory valuation methods

Imagine having a warehouse full of inventory items all exactly the same. A customer reaches out, and you agree to sell one piece from your inventory. How do you figure out the exact cost of that inventory item, especially if your inventory costs have changed over time? You have several options to choose from.

First-in, first-out

First-in, first-out (FIFO) is a method of inventory valuation where the first units added to the inventory are the first ones sold. The cost of goods sold is calculated based on the cost of the oldest inventory, while the ending inventory is valued at the cost of the most recently acquired items.

Let’s look at an example. You own a company and have 50 items in inventory: 25 items from Batch A were made last month at $10/each. 25 items from Batch B were made this month and cost $12/each to make. Both batches made the exact same good.

Under FIFO, the first goods made were from Batch A. Therefore, if you sold 10 units of inventory, your cost of goods sold would be $100 (10 units * $10 each). Your inventory balance would then be the remaining 15 units at $10 each in addition to the 25 units at $12 each.

FIFO is often considered more intuitive as it usually resembles the natural flow of goods through inventory. In periods of rising prices, FIFO tends to result in a lower cost of goods sold and a higher reported net income, as the older, lower-cost inventory is matched with current higher selling prices. This may result in higher taxes in the short term.

Last-in, first-out

Another option is the last-in, first-out (LIFO) method. LIFO assumes the last units added to the inventory are the first ones sold. This means that the cost of goods sold reflects the most recent costs, while the ending inventory is valued at the cost of the oldest items.

Let’s run with the example above again. This time, under the LIFO method, the 10 units sold would have come from the batch made this month costing $12/each. Cost of goods sold would have been $120, and your inventory balance would be all 25 units from Batch A at $10/each and the 15 units remaining from Batch B at $12/each.

LIFO is particularly helpful in times of inflation, as it matches the higher current costs with revenue. This may mean lower taxable income. However, LIFO can lead to inventory valuation challenges and do not always reflect the physical flow of goods. For example, grocery stores may naturally try to sell their oldest goods first to avoid older perishable goods from going bad.

Average costing

Average costing involves calculating the weighted average cost of all units in inventory and applying this average cost to both the cost of goods sold and ending inventory. This method is particularly useful when there's no clear distinction between old and new inventory or when goods are interchangeable. It’s mainly used to simplify the cost allocation exercise.

Running with our example one last time, let’s now pretend the company does not care about distinguishing between Batch A and Batch B. Instead, the company aggregates all information and determines it has 50 units at an average cost of $11/each. If it sells 10 units, the cost per unit sold is $11. The company then has 40 units remaining in inventory, each at an average cost of $11.

Average costing provides a smooth and consistent cost flow that tends to moderate the effects of price fluctuations. However, it may not accurately reflect the actual cost of specific units in inventory. This is especially true when prices rise rapidly or innovative changes happen. For example, the cost to manufacture a good may dramatically change if a company invests in new technology or better raw materials. This change in cost wouldn't be captured under average costing.

Other inventory accounting considerations

There are a few other things to keep in mind when accounting for inventory. First, obsolescence has significant accounting and financial implications. When inventory becomes obsolete, it may need to be written down or completely written off, meaning it no longer has value (or as much value) on the balance sheet. There are two different methods to account for obsolescence: the direct write-off method and the allowance method. Because it doesn't adhere to the matching principle, the direct write-off method can’t be used under GAAP reporting.

In a somewhat similar theme, inventory can also be stolen. Not only would this have negative impacts on a company’s financial statements, but it also means its internal controls around protecting physical assets may be deficient. Proper internal controls not only safeguard assets but also contribute to the accuracy and reliability of financial reporting. In financial audits, an auditor may evaluate how well a company is protecting its assets (including inventory).

There’s a lot that goes into having inventory, so accountants should be aware of carrying costs that may ebb and flow. Companies often pay for insurance to cover a warehouse. There may also be maintenance, security, utility, or other carrying costs. Remember that although inventory is captured on the balance sheet as a current asset, many of these carrying costs are usually expensed when they’re incurred.

Finally, for as complex as inventory is, it makes sense that companies may implement its own inventory tracking system. Enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems or other dedicated tracking platforms can be used to track different types of inventory across the entire manufacturing and distribution process. From an accounting perspective, these systems can help maintain some of those internal controls mentioned earlier as well as help optimize inventory turnover or minimize carrying costs.

The importance of inventory

Inventory is a higher-risk financial asset worth keeping a close eye on. When accounting for inventory, both the balance sheet and the income statement are impacted. When storing inventory, there are internal controls and safeguards worth having in place. When dealing with customers, there are devastating consequences to running out of inventory. There are not many company assets that can have such broad impacts, making the accounting of inventory important to a company’s mission.

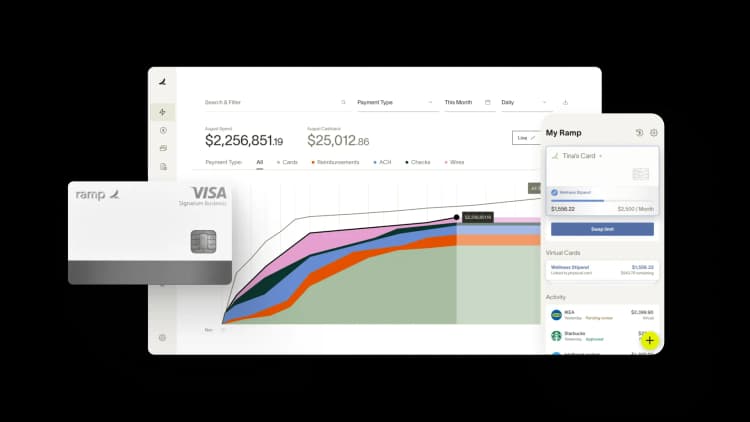

Track inventory costs automatically with Ramp's real-time spend visibility

Inventory costs are notoriously difficult to track because they involve multiple expense categories, vendors, and payment methods scattered across your organization. Without real-time visibility into purchases, you're left reconciling receipts weeks after the fact, manually coding transactions, and hoping nothing slips through the cracks.

Ramp's accounting automation software gives you complete control over inventory spending from purchase to posting. Every transaction is captured automatically, coded to the right expense account, and matched with receipts in real time—so you always know what you've spent and where it's going.

Here's how Ramp helps you manage inventory costs:

- Real-time transaction capture: Ramp records every purchase as it happens, whether it's a corporate card swipe, bill payment, or reimbursement, so inventory costs are visible immediately

- AI-powered coding: Ramp learns your accounting patterns and automatically codes inventory purchases to the correct GL accounts, cost centers, and classes—achieving a 67% increase in zero-touch codings compared to rules-only automation

- Automated receipt matching: Ramp collects and attaches receipts to transactions automatically, eliminating manual follow-up and saving 16+ hours every month

- Vendor-level tracking: Group and analyze spending by vendor to identify cost trends, negotiate better terms, and spot duplicate or unauthorized purchases

- Custom approval workflows: Set spending limits and require approvals for inventory purchases before they happen, so costs stay within budget

Try a demo to see how Ramp gives you complete visibility and control over inventory costs.

Don't miss these

“In the public sector, every hour and every dollar belongs to the taxpayer. We can't afford to waste either. Ramp ensures we don't.”

Carly Ching

Finance Specialist, City of Ketchum

“Ramp gives us one structured intake, one set of guardrails, and clean data end‑to‑end— that’s how we save 20 hours/month and buy back days at close.”

David Eckstein

CFO, Vanta

“Ramp is the only vendor that can service all of our employees across the globe in one unified system. They handle multiple currencies seamlessly, integrate with all of our accounting systems, and thanks to their customizable card and policy controls, we're compliant worldwide. ”

Brandon Zell

Chief Accounting Officer, Notion

“When our teams need something, they usually need it right away. The more time we can save doing all those tedious tasks, the more time we can dedicate to supporting our student-athletes.”

Sarah Harris

Secretary, The University of Tennessee Athletics Foundation, Inc.

“Ramp had everything we were looking for, and even things we weren't looking for. The policy aspects, that's something I never even dreamed of that a purchasing card program could handle.”

Doug Volesky

Director of Finance, City of Mount Vernon

“Switching from Brex to Ramp wasn't just a platform swap—it was a strategic upgrade that aligned with our mission to be agile, efficient, and financially savvy.”

Lily Liu

CEO, Piñata

“With Ramp, everything lives in one place. You can click into a vendor and see every transaction, invoice, and contract. That didn't exist in Zip. It's made approvals much faster because decision-makers aren't chasing down information—they have it all at their fingertips.”

Ryan Williams

Manager, Contract and Vendor Management, Advisor360°

“The ability to create flexible parameters, such as allowing bookings up to 25% above market rate, has been really good for us. Plus, having all the information within the same platform is really valuable.”

Caroline Hill

Assistant Controller, Sana Benefits