Business revenue: Definition, formula, and examples

- What is business revenue?

- Types of business revenue

- How to calculate business revenue

- Where to find revenue on financial statements

- Best practices for tracking and reporting business revenue

- Close your books faster with Ramp’s AI coding, syncing, and reconciling alongside you

Business revenue is the total money your company earns from selling products or services before subtracting expenses. Often called the top line, it’s one of the clearest indicators of how much demand your business generates and how large it is operationally. Understanding how revenue works, how it’s calculated, and how it appears in financial reporting helps you make better decisions and communicate your company’s performance clearly to stakeholders.

What is business revenue?

Business revenue is the total amount of money your company earns from selling products or services during a specific period, before subtracting expenses such as payroll, rent, or materials. It appears as the first line item on your income statement, which is why it’s often called the top line.

Although people sometimes use “revenue” and “sales” interchangeably, they’re not always the same. Sales usually refer to money earned from selling goods, while revenue includes all income tied to your core operations, such as service fees, subscriptions, licensing, and recurring charges.

Revenue is a foundational metric because it reflects customer demand and the overall scale of your business. Tracking revenue over time helps you spot growth trends, seasonal patterns, and changes in pricing effectiveness.

Revenue vs. profit vs. income

Revenue is not profit, and it’s not always the same as income. Revenue measures total inflows from business activity, while profit reflects what remains after expenses are deducted. Income is a broader term that can refer to either, depending on context, though net income specifically means profit.

| Term | Definition | Also known as | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | Total money earned from sales and services before any deductions | Top line, gross sales | Sales + service fees + operating income |

| Profit | Money remaining after subtracting all expenses from revenue | Net income, bottom line, earnings | Revenue – total expenses |

| Income | Can refer to revenue or profit depending on context | Earnings, net income (when referring to profit) | Varies by context |

Here’s how the relationship works in practice: revenue minus expenses equals profit. If your bakery generates $50,000 in monthly revenue and spends $35,000 on ingredients, labor, and overhead, your profit is $15,000. The $50,000 represents your top line, while the $15,000 is your bottom line.

This distinction matters because strong revenue does not guarantee profitability. A business can generate high revenue while operating at a loss if expenses grow faster than sales. At the same time, a smaller business with lower revenue can be highly profitable through efficient cost management.

Why revenue matters for your business

Revenue plays a central role in how investors and buyers evaluate your company. Higher revenue, especially when paired with consistent growth, often leads to higher valuations because it signals market demand and scalability.

Lenders also rely on revenue when assessing loan and credit applications. They want confidence that your business generates enough income to support repayment, and a stable revenue history can improve approval odds and borrowing terms.

Beyond external stakeholders, revenue informs everyday business decisions. By analyzing which products or services generate the most revenue, you can prioritize investments, adjust pricing strategies, and allocate resources more effectively.

Types of business revenue

Most businesses earn revenue from more than one source. Separating revenue into categories helps you understand where your income comes from and how reliable each stream is. This breakdown also gives investors and lenders a clearer picture of your core business performance.

Operating revenue

Operating revenue comes from your company’s primary business activities, the products or services you exist to sell. For a restaurant, this includes food and beverage sales. For a software company, it’s subscription fees and license sales.

You can identify operating revenue by focusing on activities that directly deliver value to customers. A retail store’s operating revenue includes merchandise sales but not interest earned on cash balances. A consulting firm’s operating revenue includes client fees but excludes income from selling unused equipment.

Examples of operating revenue vary by industry. Manufacturers earn it through product sales, law firms through billable hours and retainers, e-commerce businesses through transactions and subscriptions, and service providers through appointments or contracts.

Non-operating revenue

Non-operating revenue comes from activities outside your core business operations. While it still contributes to total income, it’s usually less predictable and not tied to your primary offering.

Common sources of non-operating revenue include:

- Interest earned on savings or money market accounts

- Dividend income from investments

- Gains from selling assets such as vehicles, equipment, or real estate

- Rental income from unused office space

- Royalties from licensing intellectual property

Companies track non-operating revenue separately so stakeholders can evaluate how well the core business performs on its own. This separation makes it easier to assess sustainability and long-term growth potential.

Gross revenue vs. net revenue

Gross revenue is the total amount customers pay before any deductions. Net revenue reflects what remains after subtracting returns, refunds, discounts, and allowances. Both are useful revenue figures, but they serve different purposes.

Gross revenue helps you understand total sales volume and customer demand. Net revenue provides a more accurate view of how much income your business actually retains and uses for planning and forecasting.

Returns and discounts directly reduce net revenue. For example, if your business generates $50,000 in gross sales in a month, issues $3,000 in refunds, and offers $2,000 in discounts, your net revenue is $45,000.

How to calculate business revenue

At its core, revenue measures how much you sell and how much customers pay. While the details vary by business model, the underlying calculation follows the same logic.

Revenue calculation for product-based businesses

For product-based businesses, revenue starts with a simple formula:

Revenue = Quantity sold * Selling price

If you sell 500 units of a product at $40 each, your revenue is $20,000.

When you sell multiple products, calculate revenue for each item and add the totals together. A hardware store that sells 200 hammers at $25 and 150 drills at $80 earns $5,000 from hammers and $12,000 from drills, for total revenue of $17,000.

Here’s a fuller example: Your online store sells three products in a month. You sell 500 units of Product A at $20, 300 units of Product B at $45, and 150 units of Product C at $80. Your total revenue is $10,000 plus $13,500 plus $12,000, or $35,500.

Revenue calculation for service-based businesses

Service businesses calculate revenue based on how they charge customers. Hourly services multiply hours worked by hourly rates, while project-based businesses recognize revenue when deliverables or milestones are completed.

Recurring revenue models such as subscriptions or retainers provide more predictable income. A marketing agency that charges $5,000 per month generates $60,000 in annual recurring revenue (ARR) per client. SaaS companies often track monthly recurring revenue (MRR) by multiplying subscription fees by active customers.

For example, a consulting firm that bills 500 hours at $150 per hour and completes two fixed-price projects worth $25,000 each earns $75,000 from hourly work and $50,000 from projects, for total revenue of $125,000.

Calculating annual business revenue

Annual revenue reflects your total revenue over a 12-month period. The most straightforward approach is to add up all monthly revenue figures from January through December.

If your revenue fluctuates seasonally, annualizing requires more care. Rather than multiplying a strong month by 12, review historical data to understand seasonal patterns and project forward based on comparable periods.

When you need an estimate midyear, you can multiply average monthly revenue by 12 for a rough projection. Quarterly revenue can also be annualized by multiplying by four, though this works best for businesses with relatively consistent revenue throughout the year.

Where to find revenue on financial statements

Revenue appears on your income statement as the first line item, making it easy to locate and track over time. Because it sits at the top, accountants often refer to it as the top line. Every profitability metric that follows starts with this number.

Revenue on the income statement

Revenue sits at the top of the income statement because it represents the total inflow from business activity before any costs are deducted. Expenses, operating income, and net income are all calculated below it.

| Line item | Amount |

|---|---|

| Revenue | |

| Product sales | $450,000 |

| Service revenue | $175,000 |

| Total revenue | $625,000 |

| Cost of goods sold | $280,000 |

| Gross profit | $345,000 |

| Operating expenses | |

| Salaries and wages | $120,000 |

| Rent | $36,000 |

| Marketing | $28,000 |

| Utilities | $12,000 |

| Insurance | $15,000 |

| Total operating expenses | $211,000 |

| Operating income | $134,000 |

| Non-operating income | |

| Interest income | $3,500 |

| Gain on asset sale | $8,000 |

| Total non-operating income | $11,500 |

| Income before taxes | $145,500 |

| Income tax expense | $36,375 |

| Net income | $109,125 |

Income statements often break revenue into multiple categories based on how a business operates. Product and service revenue may appear on separate lines, and companies with multiple divisions may report revenue by segment. This breakdown helps readers understand which parts of the business generate the most income.

When reviewing revenue, always check the reporting period. Monthly statements show revenue for a single month, while annual statements reflect a full year. Comparing periods side by side helps you identify growth trends, seasonality, or declines in specific revenue streams.

Understanding revenue recognition

Revenue recognition determines when revenue is officially recorded on your financial statements. In general, revenue is recognized when it’s earned and payment is reasonably assured, not necessarily when cash is received.

Under cash accounting, revenue is recorded when payment hits your account. Under accrual accounting, revenue is recorded when goods or services are delivered, even if payment comes later.

For example, if a consulting firm completes a $50,000 project in December but receives payment in January, the revenue appears in December under accrual accounting and January under cash accounting. This timing affects financial statements, taxes, and how stakeholders evaluate performance.

Best practices for tracking and reporting business revenue

Accurate revenue tracking depends on clear processes, reliable systems, and consistent review. When revenue data is clean and up to date, it’s easier to make decisions, apply for financing, and communicate performance to stakeholders. Small process gaps can lead to distorted numbers and poor conclusions.

Setting up revenue tracking systems

The right accounting software can automate much of your revenue tracking and reduce manual errors. Tools such as QuickBooks, FreshBooks, or Xero connect directly to bank accounts and payment processors. Larger organizations often use enterprise systems such as NetSuite or SAP for more advanced reporting and controls.

Set up revenue categories that reflect how you actually analyze performance. You might separate product and service revenue or break revenue down by region, customer type, or sales channel. Clear categorization makes it easier to spot growth opportunities and underperforming areas.

Review revenue regularly rather than waiting for month-end or quarter-end close. Weekly check-ins help catch issues early and give you more time to adjust pricing, sales strategies, or forecasts.

Revenue reporting for different stakeholders

Investors focus on revenue growth, consistency, and performance against projections. They want to understand whether growth is repeatable and which parts of the business are driving it. Year-over-year comparisons and segment-level breakdowns provide useful context.

Lenders evaluate revenue to assess repayment capacity. They typically ask for historical revenue data and may request explanations for volatility, seasonality, or one-time spikes. Clear documentation and consistent reporting improve credibility and approval odds.

Internal teams use revenue data to guide day-to-day decisions. Sales teams track revenue by rep or territory, operations teams use forecasts to plan staffing and inventory, and leadership teams rely on high-level trends with the ability to drill into details when needed.

Common revenue tracking mistakes to avoid

Even experienced teams can misstate revenue if processes aren’t consistent. Common mistakes include:

- Mixing operating revenue with non-operating income, which obscures core business performance

- Applying cash and accrual accounting inconsistently across transactions

- Failing to account for returns, refunds, and discounts, which overstates actual revenue

Avoiding these issues helps keep financial records accurate and builds confidence with investors, lenders, and internal stakeholders.

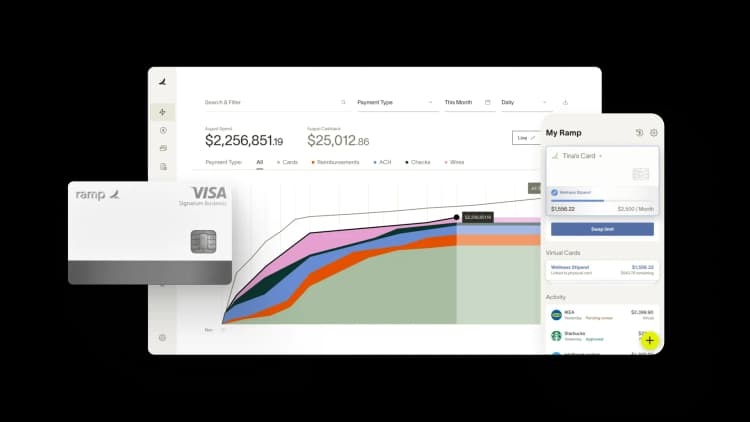

Close your books faster with Ramp’s AI coding, syncing, and reconciling alongside you

Month-end close is a stressful exercise for many companies, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Ramp’s AI-powered accounting tools handle everything from transaction coding to ERP sync, so teams close faster every month with fewer errors, less manual work, and full visibility.

Every transaction is coded in real time, reviewed automatically, and matched with receipts and approvals behind the scenes. Ramp flags what needs human attention and syncs routine, in-policy spend so teams can move fast and stay focused all month long. When it’s time to wrap, Ramp posts accruals, amortizes transactions, and reconciles with your accounting system so tie-out is smoother and books are audit-ready in record time.

Here’s what accounting looks like on Ramp:

- AI codes in real time: Ramp learns your accounting patterns and applies your feedback to code transactions across all required fields as they post

- Auto-sync routine spend: Ramp identifies in-policy transactions and syncs them to your ERP automatically, so review queues stay manageable, targeted, and focused

- Review with context: Ramp reviews all spend in the background and suggests an action for each transaction, so you know what’s ready for sync and what needs a closer look

- Automate accruals: Post (and reverse) accruals automatically when context is missing so all expenses land in the right period

- Tie out with confidence: Use Ramp’s reconciliation workspace to spot variances, surface missing entries, and ensure everything matches to the cent

Try an interactive demo to see how businesses close their books 3x faster with Ramp.

FAQs

Net income and revenue are not the same. Revenue is the total income generated from sales, while net income is the profit remaining after you deduct all operating expenses from revenue.

Revenue can be classified in a few ways:

- Operating revenue comes from your core business activities, such as selling products or providing services

- Non-operating revenue includes income from sources such as interest or rental income

Recurring vs. non-recurring revenue and cash vs. accrual-based revenue depend on your business model and accounting method.

Annual business revenue doesn’t directly determine how much tax you owe, but it plays a role in calculating your taxable income. The IRS uses your revenue, along with your expenses, deductions, and business structure, to determine your final tax liability. Higher revenue can also affect your eligibility for certain tax credits or thresholds.

“In the public sector, every hour and every dollar belongs to the taxpayer. We can't afford to waste either. Ramp ensures we don't.”

Carly Ching

Finance Specialist, City of Ketchum

“Ramp gives us one structured intake, one set of guardrails, and clean data end‑to‑end— that’s how we save 20 hours/month and buy back days at close.”

David Eckstein

CFO, Vanta

“Ramp is the only vendor that can service all of our employees across the globe in one unified system. They handle multiple currencies seamlessly, integrate with all of our accounting systems, and thanks to their customizable card and policy controls, we're compliant worldwide. ”

Brandon Zell

Chief Accounting Officer, Notion

“When our teams need something, they usually need it right away. The more time we can save doing all those tedious tasks, the more time we can dedicate to supporting our student-athletes.”

Sarah Harris

Secretary, The University of Tennessee Athletics Foundation, Inc.

“Ramp had everything we were looking for, and even things we weren't looking for. The policy aspects, that's something I never even dreamed of that a purchasing card program could handle.”

Doug Volesky

Director of Finance, City of Mount Vernon

“Switching from Brex to Ramp wasn't just a platform swap—it was a strategic upgrade that aligned with our mission to be agile, efficient, and financially savvy.”

Lily Liu

CEO, Piñata

“With Ramp, everything lives in one place. You can click into a vendor and see every transaction, invoice, and contract. That didn't exist in Zip. It's made approvals much faster because decision-makers aren't chasing down information—they have it all at their fingertips.”

Ryan Williams

Manager, Contract and Vendor Management, Advisor360°

“The ability to create flexible parameters, such as allowing bookings up to 25% above market rate, has been really good for us. Plus, having all the information within the same platform is really valuable.”

Caroline Hill

Assistant Controller, Sana Benefits