Cost of goods sold (COGS): Definition and how to calculate

- What is cost of goods sold (COGS)?

- Why COGS matters for margins, cash flow, and taxes

- How to calculate cost of goods sold with the COGS formula

- Step-by-step COGS calculation

- What’s included and not included in COGS

- FIFO, LIFO, weighted average, and specific identification

- Inventory changes and their impact on COGS

- How COGS appears in accounting systems

- COGS examples for retail, manufacturing, and SaaS

- Metrics and decisions that use COGS

- Common mistakes and limitations of COGS reporting

- Automating COGS tracking and approvals

- Automate COGS tracking with AI-powered coding

Cost of goods sold (COGS) directly affects your bottom line. It appears just below revenue on your income statement and forms the starting point for measuring gross profit.

Getting COGS right matters for three reasons: it determines your gross profit margin, influences cash flow, and reduces taxable income. Whether you’re running a small business or managing a large operation, this number guides how you price products, manage inventory, and plan for growth.

What is cost of goods sold (COGS)?

Cost of goods sold (COGS) is the total of direct costs tied to producing or acquiring the goods a business sells in a given period. It includes raw materials, direct labor, and other expenses required to get products ready for sale.

On the income statement, COGS is the first expense line after revenue. Subtracting it from revenue gives you gross profit—a key measure of how efficiently you turn sales into earnings. For manufacturers, COGS covers raw materials and factory labor; for retailers, it’s the wholesale cost of inventory sold.

Unlike overhead costs or administrative expenses, which fall under selling, general, and administrative expenses (SG&A) or operating expenses (OpEx), COGS includes only expenses directly linked to production or resale. It’s one of the most important metrics for understanding profitability and managing margins.

Why COGS matters for margins, cash flow, and taxes

COGS influences three critical areas of your business: profitability, cash flow, and taxes. Each of these factors shapes your company’s financial health and day-to-day decisions.

- Gross profit and margins: Revenue minus COGS equals gross profit. Lower COGS means higher gross profit margin and healthier net income.

- Cash flow impact: You often pay for raw materials or inventory before making a sale. This timing gap affects working capital and can strain cash flow if not managed carefully.

- Tax deductions: The IRS allows businesses to deduct COGS from revenue, a tax deduction that lowers taxable income dollar for dollar. Accurate reporting ensures compliance with Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) and prevents overpaying taxes.

Managing COGS effectively helps maintain healthy margins, stable cash flow, and accurate tax reporting, which are all essential to sustainable growth.

How to calculate cost of goods sold with the COGS formula

The standard COGS formula is:

Cost of goods sold = Beginning inventory + Purchases – Ending inventory

This calculation shows the direct costs of goods you actually sold during the accounting period, not just what you purchased.

COGS calculation example

A clothing store starts the month with $10,000 in inventory. During the month, it buys $15,000 more. At month-end, $8,000 of inventory remains.

- Beginning inventory: $10,000

- Purchases: $15,000

- Ending inventory: $8,000

- COGS = $10,000 + $15,000 – $8,000 = $17,000

This $17,000 represents the total cost of merchandise sold during the month. If sales revenue was $30,000, gross profit would equal $13,000 ($30,000 – $17,000).

This basic calculation forms the foundation for understanding gross profit and other key financial metrics. In the next section, we’ll break down how to apply it step by step for consistent, accurate reporting.

Step-by-step COGS calculation

Breaking down the COGS calculation into steps helps ensure accuracy and catch potential errors. Follow this process for consistent results during each accounting period:

1. Confirm beginning inventory balance

Use the prior period’s ending inventory as your beginning balance. Pull it from the balance sheet and your inventory report, then reconcile to the general ledger. Investigate any write-downs, shrinkage, or pending adjustments before you proceed.

2. Add purchases or production costs

Sum all inventory purchases during the period, including freight-in. For manufacturers, add production costs: raw materials, direct labor, and manufacturing overhead. Exclude SG&A and other operating expenses. Clean bookkeeping here prevents overstating inventory value and understating COGS.

3. Count and value ending inventory

Perform a physical count (or cycle counts) and reconcile to your perpetual records. Remove damaged or obsolete items or record write-downs. To assign costs to items on hand, apply your inventory valuation method:

- First-in, first-out (FIFO)

- Last-in, first-out (LIFO)

- Weighted average

- Specific identification

This choice affects financial statements, taxes, and profitability.

4. Apply the COGS formula and verify results

Use the COGS formula and review the result against sales volume and historical gross profit margin. If COGS looks high or low, recheck cutoff timing, count accuracy, and valuation method settings.

Quick checks

- Match inventory decreases on the balance sheet to COGS increases on the income statement

- Verify you’ve included freight-in and excluded freight-out

- Confirm direct costs sit in COGS and indirect costs stay in opex

Following this process consistently keeps your financial statements accurate and your COGS reporting reliable period after period.

What’s included and not included in COGS

COGS only includes direct costs tied to producing or acquiring products for sale. Operating expenses, such as marketing and administrative costs, stay separate on your income statement.

Included in COGS

- Raw materials and merchandise purchases: For retailers, this means wholesale inventory costs; for manufacturers, it includes the materials consumed in production

- Direct labor: Wages for workers who physically create products, such as factory staff, bakers, or seamstresses. These are variable costs that rise and fall with production.

- Factory overhead tied to production: Rent for the production facility, utilities that power equipment, depreciation of machinery, and quality control or maintenance costs

- Supervisory and production support costs: Salaries of floor supervisors or line managers whose work is directly tied to manufacturing output

- Freight-in: Shipping charges to acquire raw materials or inventory from suppliers. These costs increase the value of your inventory.

- Packaging materials: Boxes, protective wrap, labels, or any materials essential to preparing a product for customer delivery

Excluded from COGS

- Marketing and advertising expenses: Campaigns that promote products but don’t physically create them

- Administrative expenses: Office staff wages, management salaries, and other indirect labor costs

- Office rent and insurance: General business overhead not linked directly to manufacturing or resale

- Professional services: Legal, accounting, and customer service costs

- Freight-out: Shipping expenses to deliver goods to customers after the sale

- Sales commissions and other indirect costs: Compensation tied to selling, not producing, goods

If a cost exists only because you’re producing or acquiring products, it belongs in COGS. If it supports the business overall, it stays in OpEx or SG&A.

FIFO, LIFO, weighted average, and specific identification

How you value inventory directly determines how much cost flows into COGS and, in turn, how much profit you report. Different valuation methods change your taxable income, reported margins, and how investors interpret your results.

| Method | Definition | Impact on COGS & profitability | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|

| FIFO (First-in, first-out) | Records oldest inventory costs as sold first | Produces lower COGS and higher reported profits when prices rise, which increases taxable income | Perishable goods or businesses that need IFRS compliance |

| LIFO (Last-in, first-out) | Records newest inventory costs as sold first | Produces higher COGS and lower taxable income during inflation, reducing reported profits. Not permitted under IFRS. | U.S. companies seeking IRS tax advantages |

| Weighted average | Blends all unit costs into a single average cost per item | Smooths out price fluctuations and creates stable gross margins | Businesses with interchangeable items, bulk production, or commodity inputs |

| Specific identification | Tracks the actual cost of each unique item sold | Provides the most precise COGS but requires detailed recordkeeping | High-value or unique products such as jewelry, cars, or custom furniture |

Your valuation method doesn’t just affect accounting—it shapes your taxes and profitability. Once you choose one, you’ll need to use it consistently unless the IRS grants approval to change. Under IFRS, only FIFO and weighted average are allowed.

Inventory changes and their impact on COGS

Changes in inventory levels directly affect your cost of goods sold:

- Inventory increases lower COGS: When ending inventory is higher than beginning inventory, more costs stay on the balance sheet instead of flowing into COGS. This defers expenses and raises reported profitability.

- Inventory decreases raise COGS: When ending inventory is lower than beginning inventory, more costs move into COGS. This reduces gross profit but can improve cash flow as inventory converts to sales.

Understanding this relationship helps you manage working capital and anticipate shifts in your margins. Strategic inventory management balances profitability and liquidity: Building stock ties up cash but delays expense recognition, while leaner operations free cash faster but increase COGS sooner.

nventory management isn’t just about stock levels—it directly influences profitability, cash flow, and tax reporting through COGS.

How COGS appears in accounting systems

Cost of goods sold appears on the income statement directly below revenue as an expense line. Its placement highlights its role in determining gross profit, the first and most visible measure of profitability.

In your chart of accounts, COGS is an expense account that increases with debits. When you sell inventory, you debit COGS and credit the inventory account, moving costs from the balance sheet to the income statement.

This process ensures expenses align with the revenue they helped generate within the same period, following the expense recognition principle as stipulated by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP).

The relationship between COGS and inventory accounts also acts as a built-in accuracy check: Decreases in inventory on the balance sheet should match increases in COGS on the income statement, adjusted for any write-downs or valuation changes.

COGS examples for retail, manufacturing, and SaaS

How COGS appears on your financials depends on the type of business you run. The same formula applies across industries, but the costs that feed into it vary. These examples show how it works in practice for retail, manufacturing, and SaaS companies.

Brick-and-mortar retail example

A clothing store starts the quarter with $50,000 in inventory. It purchases $120,000 in merchandise and pays $3,000 in freight-in. Quarter-end inventory is $45,000.

COGS = $50,000 + $120,000 + $3,000 – $45,000 = $128,000

If sales were $250,000, gross profit equals $122,000, producing a 48.8% gross margin.

Light manufacturing example

A furniture maker begins with $20,000 in raw materials. It buys $40,000 more, incurs $30,000 in direct labor, and $10,000 in factory overhead. Ending materials and work-in-process total $15,000.

COGS = $20,000 + $40,000 + $30,000 + $10,000 – $15,000 = $85,000

This represents the total production cost of furniture sold during the period.

SaaS example

Software-as-a-service companies are a somewhat unique example because they don't produce any physical goods. As a result, they have no real inventory to aid in calculating COGS.

Nevertheless, they would report the costs associated with creating and delivering software as COGS, including hosting expenses, wages and salaries for engineers, and third-party software fees.

For example, in a typical month, a SaaS startup might spend $1,000 for hosting on AWS, $32,000 in salary for a team of two engineers, and $300 for developer tools to aid in building the software. Their monthly COGS would be $33,300.

Metrics and decisions that use COGS

Cost of goods sold shapes several key financial metrics that guide pricing, inventory management, and profitability planning.

Gross profit and gross margin

Gross profit equals revenue minus COGS. Gross margin expresses this relationship as a percentage of sales.

Gross profit margin = (Revenue – COGS) / Revenue * 100

A 60% gross profit margin means you keep $0.60 of every sales dollar after covering direct costs. Tracking this trend over time helps you spot rising costs, shrinking margins, or pricing pressure.

Inventory turnover

Inventory turnover measures how efficiently you sell through stock over time. It’s calculated using the following formula:

Inventory turnover = COGS / Average inventory

A turnover ratio of 12 means you sell inventory roughly once per month; a ratio of 4 means once per quarter. Higher turnover usually improves cash flow and reduces the risk of excess stock.

Break-even price point

Your break-even price must cover COGS plus a share of operating expenses. Selling below COGS means losing money on every unit.

Contribution margin analysis—price minus COGS—shows how much each sale contributes toward fixed costs and profit. It’s essential for pricing, discounting, and promotion planning.

Common mistakes and limitations of COGS reporting

Accurate cost of goods sold reporting is critical for reliable financial statements. But businesses often make errors that distort profitability and tax reporting.

Frequent mistakes

- Including indirect costs: Administrative salaries, marketing spend, or other SG&A expenses sometimes get misclassified as COGS

- Missing invoices or freight-in charges: Overlooking supplier bills or shipping costs understates inventory value and skews COGS

- Timing mismatches: Inventory counts that don’t align with the accounting period can shift expenses into the wrong month or quarter

- Inconsistent inventory valuation methods: Switching between FIFO, LIFO, and weighted average without approval undermines reporting accuracy

- Ignoring damaged or obsolete inventory: Failing to adjust for shrinkage, spoilage, or write-downs overstates ending inventory and understates COGS

Even when COGS is calculated correctly, it has its limits. It only measures direct costs, excluding other factors that affect true profitability.

Limitations to keep in mind

- COGS doesn’t capture customer acquisition costs, product development, or indirect expenses

- Gross margin alone won’t show if a product line is profitable once you allocate overhead costs

- Financial analysis should pair COGS data with operating expenses, SG&A, and cash flow insights to see the full picture of business health

Understanding these limits makes it easier to combine COGS data with automation tools and financial dashboards—the next step toward more accurate reporting.

Automating COGS tracking and approvals

Tracking cost of goods sold manually leaves too much room for mistakes and lagging data. Automation keeps your books accurate, updates reports in real time, and gives you clear visibility into margins as spending happens.

Live data sync from spend cards

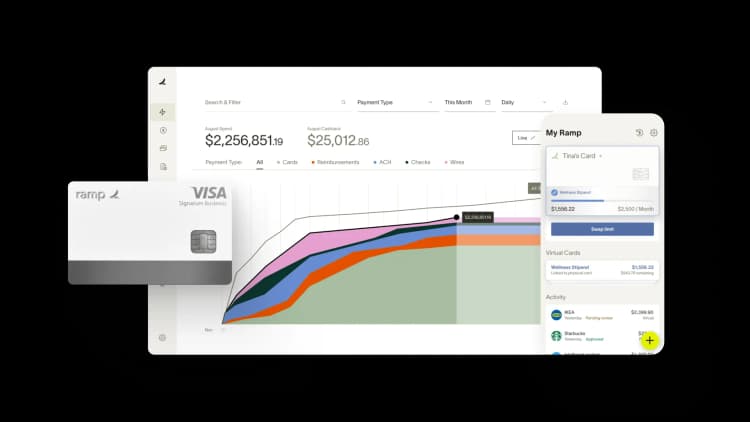

Ramp's corporate cards offer built-in expense categorization that automatically separates COGS purchases from operating expenses. When employees buy raw materials, packaging, or resale inventory, those transactions flow directly into the COGS account.

Real-time sync eliminates manual data entry, reduces mistakes, and helps you track production costs as they occur instead of waiting for month-end reconciliation.

Automated invoice matching

Three-way matching between purchase orders, receiving reports, and invoices prevents duplicate payments and keeps your accounting period aligned. AP automation platforms like Ramp Bill Pay handle this automatically, ensuring every inventory cost appears in COGS correctly. By integrating with inventory systems, you can keep your balance sheets and income statements accurate.

Real-time margin dashboards

Automated dashboards show how COGS affects gross profit margin without waiting weeks for financial statements to close. You can analyze results by product, customer, or location and quickly identify margin erosion, cost increases, or pricing challenges.

With tools like Ramp’s real-time reporting, these insights surface as transactions happen, letting you adjust pricing strategies before profitability suffers.

Built-in approval workflows

Automation tools also create controls around COGS-related spending. Approval hierarchies ensure only valid direct costs flow into your COGS account, while unauthorized or indirect expenses stay in SG&A or other operating expense categories. This distinction keeps financial reporting accurate and cash flow forecasts dependable.

Automate COGS tracking with AI-powered coding

Calculating COGS accurately requires tracking every purchase, labor cost, and overhead expense tied to production—a process that's time-consuming and error-prone when done manually. Misclassified transactions can distort your gross margin, throw off inventory valuations, and create compliance headaches during audits.

Ramp's AI-powered accounting software eliminates manual COGS tracking by coding every transaction in real time across all required fields. The platform learns your accounting patterns and applies your feedback to categorize transactions automatically as they post. You'll see COGS-related spend coded correctly from day one, with AI that flags only the exceptions that need human review.

Here's how Ramp streamlines COGS management:

- AI codes transactions instantly: Ramp applies your chart of accounts and coding rules to categorize COGS components as transactions occur

- Auto-sync routine spend: Ramp identifies in-policy COGS transactions and syncs them to your ERP automatically, so your inventory and expense accounts stay current without manual data entry

- Review with full context: Every transaction includes receipts, approvals, and vendor details in one place, so you can verify COGS classifications quickly and adjust as needed

- Track by project or product: Use custom fields and tags to allocate COGS to specific products, jobs, or cost centers, giving you granular visibility into profitability

Try an interactive demo to see how Ramp automates COGS tracking and helps finance teams clear their accounting queue 3x faster every month.

FAQs

Only direct labor wages for workers who make or prepare products count as COGS. Office staff, management, and other administrative expenses remain in operating expenses (SG&A).

COGS appears on the income statement as the first expense line after revenue. Subtracting it from revenue gives you gross profit, which is then used to calculate gross profit margin.

Cost of revenue includes COGS plus additional direct costs, such as sales commissions and shipping goods to customers. COGS is narrower, covering only the direct costs of creating or acquiring products for sale.

Most businesses calculate COGS monthly for management reporting and annually for tax purposes. Reviewing it quarterly helps identify issues early and ensures your accounting period reflects accurate margins.

“In the public sector, every hour and every dollar belongs to the taxpayer. We can't afford to waste either. Ramp ensures we don't.”

Carly Ching

Finance Specialist, City of Ketchum

“Ramp gives us one structured intake, one set of guardrails, and clean data end‑to‑end— that’s how we save 20 hours/month and buy back days at close.”

David Eckstein

CFO, Vanta

“Ramp is the only vendor that can service all of our employees across the globe in one unified system. They handle multiple currencies seamlessly, integrate with all of our accounting systems, and thanks to their customizable card and policy controls, we're compliant worldwide. ”

Brandon Zell

Chief Accounting Officer, Notion

“When our teams need something, they usually need it right away. The more time we can save doing all those tedious tasks, the more time we can dedicate to supporting our student-athletes.”

Sarah Harris

Secretary, The University of Tennessee Athletics Foundation, Inc.

“Ramp had everything we were looking for, and even things we weren't looking for. The policy aspects, that's something I never even dreamed of that a purchasing card program could handle.”

Doug Volesky

Director of Finance, City of Mount Vernon

“Switching from Brex to Ramp wasn't just a platform swap—it was a strategic upgrade that aligned with our mission to be agile, efficient, and financially savvy.”

Lily Liu

CEO, Piñata

“With Ramp, everything lives in one place. You can click into a vendor and see every transaction, invoice, and contract. That didn't exist in Zip. It's made approvals much faster because decision-makers aren't chasing down information—they have it all at their fingertips.”

Ryan Williams

Manager, Contract and Vendor Management, Advisor360°

“The ability to create flexible parameters, such as allowing bookings up to 25% above market rate, has been really good for us. Plus, having all the information within the same platform is really valuable.”

Caroline Hill

Assistant Controller, Sana Benefits