Economic order quantity (EOQ): Formula and examples

- What is the EOQ formula?

- How to calculate EOQ: Step-by-step guide

- EOQ formula components: Deep dive

- EOQ formula assumptions and limitations

- EOQ calculators and tools

- EOQ: Practical applications and examples

- Automate inventory spend analysis with Ramp

Economic order quantity (EOQ) is a formula used to calculate the optimal order size that minimizes total inventory costs, including ordering and holding costs.

If you’ve ever faced the tension between overstocking and stockouts, you’ve already seen the problem EOQ is designed to solve: ordering too often increases administrative and shipping costs, while ordering too much ties up cash and increases storage risk. For financial operations teams, EOQ provides a practical way to make inventory decisions more predictable and directly connected to cash flow.

What is the EOQ formula?

The economic order quantity formula calculates how many units you should order each time to minimize your total inventory costs. It balances the cost of placing orders against the cost of holding inventory so you’re not overordering or reordering too frequently.

The EOQ formula is:

EOQ = √[(2 * D * S) / H]

Where:

- D is annual demand

- S is the cost per order

- H is the annual holding cost per unit

In practice, EOQ answers one question: How many units should you order per purchase to keep your combined ordering and holding costs as low as possible?

The EOQ model was first introduced by Ford W. Harris in 1913 to optimize production lot sizes. More than a century later, it’s still widely used because the tradeoff between ordering costs and holding costs hasn’t changed.

Understanding the EOQ variables

Annual demand (D) represents how many units you expect to sell or use in a year. For example, a retailer selling 1,000 units of a product annually would use D = 1,000. This figure should reflect realistic demand based on historical data, not aspirational forecasts.

Ordering cost (S) includes every cost incurred each time you place an order, regardless of order size. Common components include:

- Procurement processing time, such as purchase order creation and approvals

- Shipping and receiving costs tied to inbound orders

- Inspection and reconciliation effort once goods arrive

Holding cost (H) is the annual cost of holding one unit in inventory. It typically includes storage, insurance, shrinkage, and the opportunity cost of capital tied up in inventory. Many businesses estimate holding cost as a percentage of the item’s unit value, often 15–30%, and then convert that percentage into a dollar amount per unit per year.

| Variable | Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| D | Annual demand (units per year) | 1,000 units |

| S | Ordering cost per order | $2 per order |

| H | Annual holding cost per unit | $5 per unit |

What EOQ minimizes: total annual inventory cost

EOQ works because it minimizes your total annual inventory cost, which combines the cost of placing orders with the cost of holding inventory over time.

Total annual inventory cost can be expressed as:

Total annual inventory cost = (D / Q) * S + (Q / 2) * H

Where Q is the order quantity in units.

The first term represents total ordering cost for the year, based on how often you place orders. The second term represents total holding cost, based on the average inventory you carry. EOQ is the value of Q that minimizes this combined cost.

How to calculate EOQ: Step-by-step guide

Calculating EOQ isn’t complicated, but it does require disciplined inputs. The formula only works if demand, ordering costs, and holding costs are measured consistently and expressed on the same annual basis.

Before you calculate EOQ, make sure you’re using annualized figures and that you’ve captured all costs tied to placing and holding inventory, not just the obvious ones.

- Estimate annual demand (D) using historical sales or usage data

- Calculate ordering cost per order (S) by summing all fixed costs tied to placing an order

- Estimate annual holding cost per unit (H)

- Plug the values into the EOQ formula

- Interpret the result as units per order

Once you’ve worked through these steps, EOQ gives you a repeatable ordering rule you can apply across products. The real value comes from revisiting the calculation as conditions change, such as when demand shifts, suppliers update pricing, or internal processes become more efficient.

EOQ isn’t a one-time answer. It’s a baseline you refine as your inventory strategy matures.

EOQ calculation example

Assume a business orders 1,000 units per year. Each order costs $2 to place, and holding one unit in inventory for a year costs $5.

- EOQ = √[(2 * D * S) / H]

- EOQ = √[(2 * 1,000 * 2) / 5]

- EOQ = √[4,000 / 5]

- EOQ = √800 ≈ 28.3 units

In this case, the cost-minimizing order size is about 28 units per order. In practice, you’d round to a workable quantity, such as 28 or 30 units.

Common calculation mistakes to avoid

Minor errors in EOQ inputs can produce misleading results:

- Mixing time periods: If demand is annual, ordering and holding costs must also be annualized, or the output won’t be meaningful

- Incorrectly calculating holding costs: Excluding capital costs or obsolescence risk understates H and pushes EOQ too high

- Forgetting ordering cost components: Ignoring internal processing time biases EOQ toward smaller, more frequent orders

EOQ formula components: Deep dive

Each EOQ variable represents a real operational decision. Estimating these inputs accurately matters more than the formula itself, because small errors can meaningfully change the result.

Annual demand (D)

Annual demand represents how many units you expect to sell or use in a year. Historical sales or usage data, adjusted for growth or contraction, is often the most reliable starting point.

Seasonality complicates demand estimation. When demand fluctuates throughout the year, EOQ still works best when applied to average annual demand, paired with separate safety stock calculations to handle variability.

Common sources for demand data include:

- Historical sales records

- Production or usage logs

- Forecasts from sales or planning teams

Ordering cost (S)

Ordering cost is the total cost of placing and receiving a single order, regardless of how many units you buy. EOQ works best when S reflects the average cost of a typical order, not just supplier pricing.

Common ordering cost components include:

- Purchase order processing and approvals, which consume staff time

- Inbound freight and receiving labor

- Vendor communication, quality checks, and invoice reconciliation

Even if these costs seem small individually, they add up quickly when orders are placed frequently. Underestimating ordering costs pushes EOQ too low, leading to excessive reordering and unnecessary administrative overhead.

Holding cost (H)

Holding cost captures the ongoing cost of keeping inventory on hand. This typically includes storage space, insurance, spoilage, and disuse.

Opportunity cost is often the largest hidden component. Capital tied up in inventory can’t be used for growth, debt reduction, or investment elsewhere.

Holding cost can be expressed either as a dollar amount per unit per year or as a percentage of unit value, which is then converted into dollars for the EOQ formula.

EOQ formula assumptions and limitations

EOQ relies on simplifying assumptions that make the math tractable. Understanding these assumptions helps you know when EOQ works well and when it needs adjustment.

EOQ assumes that:

- Demand is constant and known: This allows the model to focus on cost tradeoffs rather than forecasting uncertainty

- Replenishment is instantaneous: Inventory arrives all at once instead of gradually over time

- Ordering and holding costs are stable: Costs don’t change as order size varies

EOQ works best for stable, high-volume items with predictable demand. It becomes less reliable when demand is volatile, lead times are long, or suppliers impose rigid constraints.

Real-world adjustments

In practice, EOQ is often used alongside other inventory controls.

Quantity discounts can shift the optimal order size. In these cases, EOQ serves as a baseline, which you then compare against discounted price breaks to identify the true minimum total cost.

Lead times matter because EOQ determines how much to order, not when. Reorder points fill that gap by accounting for expected demand during replenishment.

Safety stock protects against demand variability and supply delays. EOQ sets order size, while safety stock influences how much buffer inventory you carry.

EOQ calculators and tools

EOQ calculators and spreadsheets can speed up calculations, but they only work if the underlying inputs are accurate. These tools are most useful once you understand how demand, ordering costs, and holding costs interact in the EOQ formula.

Many free EOQ calculators are available online, and most rely on the same core equation. They’re helpful for quick checks, but you should still validate the assumptions behind the numbers you enter.

In Excel, the EOQ formula looks like:

=SQRT((2 * D * S) / H)

Inventory management software can also support EOQ modeling:

- Centralized purchasing data improves demand estimates

- Automated procurement workflows reduce assumed ordering costs by streamlining approvals and processing

- Real-time visibility helps validate EOQ outputs against actual usage and spend patterns

Creating your own EOQ spreadsheet

A simple EOQ spreadsheet typically includes inputs for annual demand (D), ordering cost (S), and holding cost (H), along with calculated EOQ and total cost outputs.

By linking EOQ inputs to live sales and purchasing data, you can automatically recalculate optimal order sizes as conditions change.

EOQ: Practical applications and examples

EOQ becomes most useful when you apply it to real purchasing decisions rather than treating it as a theoretical exercise. Different industries face different constraints, from storage limitations to volatile demand patterns, and EOQ helps clarify where inventory costs are actually coming from.

EOQ in different industries

Retail businesses often use EOQ for staple SKUs with steady demand. For example, a retailer selling 10,000 units annually with moderate holding costs may reduce carrying costs by shifting from monthly bulk orders to EOQ-based ordering.

Manufacturers apply EOQ to raw materials, especially when ordering costs are high and storage space is limited.

E-commerce and dropshipping businesses may rely less on EOQ for physical inventory but still use it when holding private-label stock.

EOQ vs. other inventory models

EOQ is one of several inventory models used to manage stock levels, and it works best when you understand how it compares to alternatives.

| Model | Primary goal | Strengths | Limitations | Best use cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EOQ | Minimize total inventory cost | Simple, quantitative, easy to model in spreadsheets | Assumes stable demand and instant replenishment | High-volume SKUs with predictable demand and known costs |

| JIT (Just-in-Time) | Minimize inventory on hand | Reduces holding costs and storage needs | Highly sensitive to supply disruptions | Manufacturing or operations with reliable suppliers and short lead times |

| ABC analysis | Prioritize inventory management effort | Focuses attention on high-impact items | Does not determine order quantities | Portfolio-level inventory control and resource allocation |

| Safety stock models | Prevent stockouts | Absorbs demand and lead-time variability | Increases holding costs | Volatile demand or uncertain supply chains |

| EPQ (Economic Production Quantity) | Minimize production and inventory costs | Accounts for gradual replenishment | More complex than EOQ | Manufacturing operations with in-house production and steady demand |

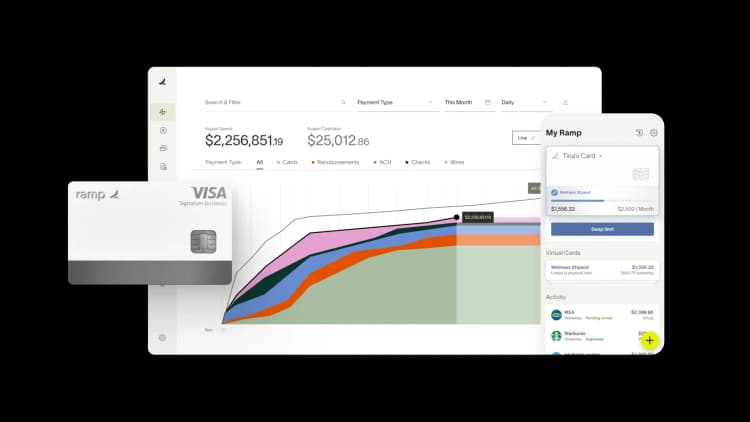

Automate inventory spend analysis with Ramp

Determining optimal order quantity requires accurate data on inventory costs, usage patterns, and supplier spend, but most teams are stuck piecing together spreadsheets, invoices, and purchase orders manually. Ramp's accounting automation software gives you real-time visibility into inventory spend and usage patterns so you can make smarter ordering decisions without the manual work.

Ramp automatically captures and codes every inventory purchase as it happens, tagging transactions with custom fields like vendor, product category, and cost center. You'll see exactly what you're spending on inventory, when orders are placed, and how costs fluctuate over time. Ramp's AI learns your coding patterns and applies them across all transactions, so inventory expenses are categorized consistently and accurately.

When it's time to analyze ordering patterns, Ramp's reporting tools surface trends in purchase frequency, order sizes, and supplier costs. You can track which items are reordered most often, identify seasonal demand shifts, and spot opportunities to consolidate orders or negotiate better terms. Ramp also flags duplicate purchases and unusual spending patterns, so you catch inefficiencies before they impact your bottom line.

With Ramp handling the data collection and categorization, you can focus on the analysis that matters: calculating economic order quantities, comparing supplier pricing, and optimizing reorder points based on actual usage data instead of guesswork.

Try a demo to see how Ramp automates inventory spend tracking and analysis.

FAQs

If demand isn’t constant, EOQ still provides a useful baseline, but it shouldn’t be used in isolation. In these cases, safety stock and reorder points become more important to account for variability and avoid stockouts.

EOQ should be recalculated whenever one of its core inputs changes in a meaningful way. That includes shifts in demand, changes in supplier pricing or shipping terms, or improvements in internal procurement efficiency that affect ordering costs.

EOQ is calculated per item, not across products. Each SKU requires its own EOQ calculation because demand patterns, costs, and storage constraints can vary significantly between items.

EOQ determines how much to order, not when to order. Reorder points fill that gap by accounting for lead time and expected demand during the replenishment period.

Supplier minimums can override EOQ by forcing you to order more than the calculated optimal quantity. In those cases, EOQ still serves as a benchmark for understanding the cost impact of that constraint and evaluating alternatives.

“In the public sector, every hour and every dollar belongs to the taxpayer. We can't afford to waste either. Ramp ensures we don't.”

Carly Ching

Finance Specialist, City of Ketchum

“Compared to our previous vendor, Ramp gave us true transaction-level granularity, making it possible for me to audit thousands of transactions in record time.”

Lisa Norris

Director of Compliance & Privacy Officer, ABB Optical

“Ramp gives us one structured intake, one set of guardrails, and clean data end‑to‑end— that’s how we save 20 hours/month and buy back days at close.”

David Eckstein

CFO, Vanta

“Ramp is the only vendor that can service all of our employees across the globe in one unified system. They handle multiple currencies seamlessly, integrate with all of our accounting systems, and thanks to their customizable card and policy controls, we're compliant worldwide. ”

Brandon Zell

Chief Accounting Officer, Notion

“When our teams need something, they usually need it right away. The more time we can save doing all those tedious tasks, the more time we can dedicate to supporting our student-athletes.”

Sarah Harris

Secretary, The University of Tennessee Athletics Foundation, Inc.

“Ramp had everything we were looking for, and even things we weren't looking for. The policy aspects, that's something I never even dreamed of that a purchasing card program could handle.”

Doug Volesky

Director of Finance, City of Mount Vernon

“Switching from Brex to Ramp wasn't just a platform swap—it was a strategic upgrade that aligned with our mission to be agile, efficient, and financially savvy.”

Lily Liu

CEO, Piñata

“With Ramp, everything lives in one place. You can click into a vendor and see every transaction, invoice, and contract. That didn't exist in Zip. It's made approvals much faster because decision-makers aren't chasing down information—they have it all at their fingertips.”

Ryan Williams

Manager, Contract and Vendor Management, Advisor360°