Expense vs. expenditure: Differences and definitions

- What is an expense?

- Types of business expenses

- How expenses impact financial statements

- What is an expenditure?

- Types of expenditures

- Expenditure recognition and timing

- Expense and expenditure: Key differences

- Capital expenditures vs. operating expenses

- Practical examples and scenarios

- Bring it all together with Ramp

An expense is a cost your business recognizes on the income statement in a specific accounting period, while an expenditure is the act of spending money to acquire goods or services, whether or not that cost is immediately expensed.

The distinction matters because expenses directly affect profit, while expenditures describe how and when cash leaves your business. Understanding the difference helps you report financial performance accurately, plan taxes, and make better spending decisions.

What is an expense?

In accounting, an expense is a cost incurred to generate revenue during a specific period. Expenses are recognized on the income statement and reduce net income, reflecting the consumption of economic benefits such as labor, utilities, or inventory.

When you recognize an expense depends on your accounting method:

- Accrual basis accounting: Recognizes accrued expenses when you incur them, not when you pay. This approach aligns costs with the revenue they help generate and follows Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) matching principles.

- Cash basis accounting: Recognizes expenses when cash leaves the business. This method is simpler but can distort profitability for growing companies.

On the income statement, expenses appear as line items that reduce gross profit and operating income. Operating expenses, cost of goods sold (COGS), and selling expenses all flow through to net income, making expense classification a key driver of reported financial performance.

Types of business expenses

Most businesses incur recurring expenses tied to daily operations and revenue generation. These costs typically recur on a monthly or quarterly basis and directly affect profitability.

Operating expenses

Operating expenses support ongoing business activities but aren’t directly tied to producing goods:

- Rent: Keeps your workspace operational and is typically recognized monthly as an expense

- Salaries and wages: Compensate employees for work performed during the period

- Utilities, insurance, and subscriptions: Support daily operations and are expensed as incurred

Cost of goods sold

Cost of goods sold (COGS) includes direct costs required to produce goods or deliver services. For a manufacturer, this includes raw materials and direct labor. For a retailer, it’s the cost of inventory sold during the period.

You recognize COGS at the point of sale, not when you purchase inventory. You might spend $100,000 on inventory in January, but none of that cost appears on the income statement until the inventory is sold. This timing aligns revenue with related costs and prevents overstated expenses in periods without sales.

Administrative expenses

Administrative expenses cover overhead costs required to run your business, regardless of sales volume. These expenses don’t directly generate revenue, but they keep the organization functional and compliant.

Because they’re ongoing and predictable, administrative expenses are often a focus area for cost control. Common examples include:

- Accounting and legal fees

- Office supplies and software subscriptions

- Human resources costs, such as automated payroll processing

- Professional licenses and continuing education fees required to operate legally

Selling expenses

Selling expenses include marketing, advertising, commissions, and sales tools. These costs aim to drive revenue but don’t directly create inventory or services.

Selling expenses often scale with growth. As revenue targets increase, businesses typically invest more in advertising, commissions, and sales infrastructure. While these costs reduce short-term profitability, they’re often evaluated through return-on-investment (ROI) metrics rather than simple expense reduction.

How expenses impact financial statements

Expenses directly reduce net income, making them central to profitability analysis. When expenses increase without corresponding revenue growth, margins compress and reported performance declines.

From a tax perspective, most operating expenses are deductible in the current period, which lowers taxable income. According to IRS Publication 334, ordinary and necessary business expenses are generally deductible in the year they’re incurred.

Expenses also follow the matching principle, which requires businesses to recognize costs in the same period as the revenue they help generate. This approach improves accuracy and comparability across reporting periods by ensuring financial statements reflect the true cost of operations.

What is an expenditure?

An expenditure is the amount your business spends to acquire goods or services, either by paying cash or by incurring a liability, such as purchasing on credit. It describes the act of spending resources, regardless of how you treat that spending in your accounting records.

Expenditures are broader than expenses. They include payments for inventory, equipment, debt principal, dividends, and capital investments. Some expenditures become expenses immediately, while others are recorded as assets and expensed over time.

All expenses are expenditures because money ultimately leaves the business. But not all expenditures are expenses. Paying down loan principal or buying a long-term asset involves a cash outflow without immediate expense recognition.

Types of expenditures

Expenditures describe how and when money leaves your business, regardless of how those payments are treated in your accounting records. Breaking expenditures into clear categories helps you understand cash requirements, avoid misclassification, and plan for short-term liquidity and long-term investment needs.

Revenue expenditures

Revenue expenditures support current operations and provide short-term benefits. These expenditures are recognized as expenses in the same accounting period, meaning they affect both cash flow and profit immediately. Rent, utilities, payroll, and routine maintenance all fall into this category.

Because revenue expenditures hit the income statement right away, they play a major role in margin management. Even small increases in recurring revenue expenditures can significantly impact profitability over time, which is why finance teams closely monitor these costs in monthly and quarterly reporting.

Capital expenditures

Capital expenditures create long-term benefits and are recorded as assets on the balance sheet. Examples include:

- Equipment purchases: Provide value over multiple years and are depreciated over their useful lives

- Buildings and property: Offer long-term benefits and are capitalized and depreciated, except for land, which doesn’t depreciate

- Major system upgrades: Extend asset life or capacity and are capitalized rather than expensed

Each of these expenditures becomes an expense gradually through depreciation or amortization, aligning cost recognition with asset usage.

Deferred expenditures

Deferred expenditures occur when you pay cash upfront, but the benefit extends over multiple periods. These payments are initially recorded as assets and then expensed gradually as the benefit is consumed. Prepaid insurance, annual software subscriptions, and prepaid rent are common examples.

This treatment prevents overstating expenses in a single period and supports more accurate profit measurement. For example, a $24,000 annual software subscription might be expensed at $2,000 per month rather than all at once.

Deferred expenditures are especially common in software-as-a-service (SaaS) businesses, where upfront payments don’t align neatly with monthly usage.

Expenditure recognition and timing

Cash leaves the business at the time of expenditure, which is reflected on the cash flow statement. Expense recognition, however, depends on accounting treatment.

Capital expenditures become expenses over time through depreciation or amortization. According to IRS Publication 946, depreciation expenses allow businesses to recover the cost of property over its useful life, rather than deducting the full amount upfront.

This separation between cash outflow and expense recognition is why businesses can report strong cash activity in one period while recognizing related expenses gradually over several years.

Expense and expenditure: Key differences

Expenses are recognized immediately or over a short period, while expenditures may be recognized over time. Expenses affect profit, while expenditures affect liquidity.

The bottom line:

- Expenses reduce profit in the current period and appear on the income statement.

- Expenditures describe what you spend, either through cash outflows or liabilities incurred.

- All expenses are expenditures, but not all expenditures are expenses.

| Aspect | Expense | Expenditure |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Cost recognized on the income statement | Cash payment or liability incurred |

| Timing | Recognized when incurred | Occurs when cash is paid or credit is used |

| Financial statement | Income statement | Cash flow statement and balance sheet |

| Impact | Reduces net income | Reduces cash or increases liabilities |

| Examples | Rent, salaries, utilities | Equipment purchase, loan payment |

Accounting treatment comparison

Journal entries differ based on how a cost is classified. When you pay $3,000 in rent, you record the full amount as an expense in the current period. When you buy long-term equipment, you record an asset first and recognize the cost gradually through depreciation.

| Scenario | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

| Monthly rent payment ($3,000) | Rent expense $3,000 | Cash $3,000 |

| Equipment purchase ($50,000) | Fixed assets (equipment) $50,000 | Cash or accounts payable $50,000 |

| Monthly depreciation | Depreciation expense | Accumulated depreciation |

On financial statements, expenses appear on the income statement, while capital expenditures initially appear on the balance sheet. The cash flow statement captures both, but in different sections:

- Operating activities: Reflect expenses paid in cash and show the cost of running the business

- Investing activities: Capture capital expenditures such as equipment purchases

- Financing activities: Include expenditures like loan repayments and dividend payments

Business decision-making impact

Expenses influence short-term budgeting and margin analysis, while expenditures shape cash planning and capital allocation. Understanding the difference helps finance teams forecast liquidity needs and avoid surprises when large payments don’t immediately appear on the income statement.

Tax planning also depends on correct classification. Expenses often provide immediate deductions, while capital expenditures generate deductions gradually through depreciation. Misclassifying these costs can distort taxable income and create compliance risk.

For investment analysis, distinguishing expenses from expenditures helps you evaluate return on investment and payback periods more accurately. A purchase that looks expensive in the short term may be justified once you account for long-term value and depreciation treatment.

Capital expenditures vs. operating expenses

Capital expenditures (CapEx) are investments in assets that provide long-term value, while operating expenses (OpEx) support day-to-day business activities. Classification typically depends on expected useful life, materiality, and internal capitalization policies.

You generally capitalize assets that provide multi-year benefits and expense routine costs that don’t extend asset life. Consistency and documentation are critical for compliance and audit readiness.

CapEx examples and treatment

Capital expenditures are recorded as assets and expensed over time through depreciation or amortization. Common examples include building purchases, equipment, and major improvements that extend asset life or capacity.

Depreciation schedules spread the cost of these assets over time:

- Straight-line depreciation: Allocates an equal expense each year

- Accelerated depreciation methods: Recognize higher expense in earlier years

- Bonus depreciation: May allow faster write-offs, subject to IRS rules

OpEx examples and treatment

Operating expenses include payroll, utilities, marketing, and routine maintenance. These costs support ongoing operations and are typically deductible in the year they’re incurred.

You generally expense maintenance and repairs unless they materially extend an asset’s useful life. Routine repairs maintain existing functionality, while minor replacements don’t qualify as capital improvements.

Practical examples and scenarios

Concrete examples make the difference between expenses and expenditures easier to apply in real situations. These scenarios show how cash movement, accounting treatment, and financial statements intersect.

Example 1: Office equipment purchase

A growing marketing agency purchases $18,000 of office equipment, including laptops and monitors, and pays cash upfront. The payment is an expenditure because cash leaves the business immediately.

Because the equipment provides value over several years, the business capitalizes the cost and assigns a useful life of three years rather than expensing it all at once. Each year, the business records $6,000 in depreciation expense on the income statement.

Over time, the expenditure becomes an expense gradually, aligning cost recognition with how the equipment contributes to revenue generation. Cash flow reflects the full payment upfront, while profit reflects the cost spread over time.

| Point in time | Cash impact | Accounting treatment |

|---|---|---|

| Purchase date | Cash decreases by $18,000 | Record $18,000 as a fixed asset |

| End of year 1 | No additional cash impact | Record $6,000 depreciation expense |

| End of year 2 | No additional cash impact | Record $6,000 depreciation expense |

| End of year 3 | No additional cash impact | Record $6,000 depreciation expense |

Example 2: Monthly rent payment

A retail business pays $4,500 in rent at the beginning of each month. The cash payment is an expenditure, and because the rent applies only to the current month, it’s also recognized immediately as an expense.

On the income statement, the $4,500 rent expense reduces operating income for the month. On the cash flow statement, the same amount appears as an operating cash outflow.

There’s no asset created because the benefit doesn’t extend beyond the rental period. When businesses prepay rent for multiple months, part of the expenditure becomes a deferred asset rather than an immediate expense, reinforcing why timing matters.

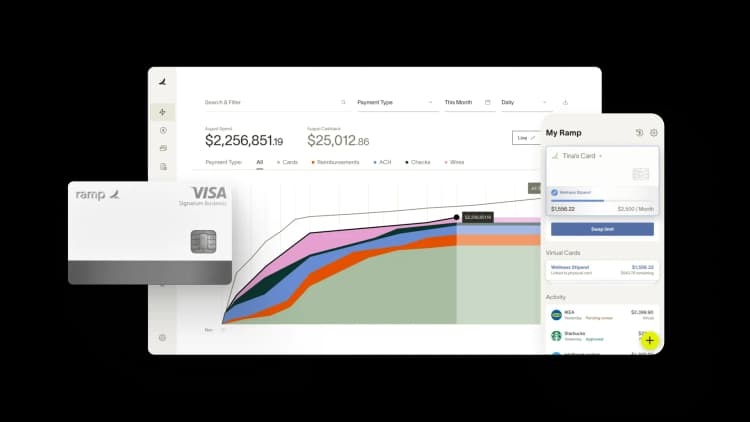

Bring it all together with Ramp

Mixing up expenses and expenditures can throw off your financial statements and create unnecessary rework. Teams often second-guess whether a software purchase should hit the income statement immediately or be capitalized, then spend hours reclassifying transactions to fix reporting errors.

Ramp’s expense management software reduces that friction through intelligent transaction classification and automated accounting workflows. The platform categorizes purchases based on your predefined rules and thresholds, helping you separate operating expenses from capital expenditures without manual intervention.

Ramp also provides real-time visibility into both expenses and expenditures through centralized reporting. You can track operating costs by department while monitoring capital investments separately, giving you clearer insight into cash flow, profitability, and spending patterns.

Try an interactive demo to see how Ramp helps finance teams stay accurate, compliant, and in control as they scale.

FAQs

Depreciation is an expense, not an expenditure. The expenditure occurs when you purchase the asset, while depreciation allocates that cost over time on the income statement.

Prepaid expenses are expenditures that become expenses over time. Cash leaves the business upfront, but expense recognition is deferred across multiple accounting periods.

Inventory purchases are expenditures initially recorded as assets. They become expenses through cost of goods sold when the inventory is sold.

“In the public sector, every hour and every dollar belongs to the taxpayer. We can't afford to waste either. Ramp ensures we don't.”

Carly Ching

Finance Specialist, City of Ketchum

“Ramp gives us one structured intake, one set of guardrails, and clean data end‑to‑end— that’s how we save 20 hours/month and buy back days at close.”

David Eckstein

CFO, Vanta

“Ramp is the only vendor that can service all of our employees across the globe in one unified system. They handle multiple currencies seamlessly, integrate with all of our accounting systems, and thanks to their customizable card and policy controls, we're compliant worldwide. ”

Brandon Zell

Chief Accounting Officer, Notion

“When our teams need something, they usually need it right away. The more time we can save doing all those tedious tasks, the more time we can dedicate to supporting our student-athletes.”

Sarah Harris

Secretary, The University of Tennessee Athletics Foundation, Inc.

“Ramp had everything we were looking for, and even things we weren't looking for. The policy aspects, that's something I never even dreamed of that a purchasing card program could handle.”

Doug Volesky

Director of Finance, City of Mount Vernon

“Switching from Brex to Ramp wasn't just a platform swap—it was a strategic upgrade that aligned with our mission to be agile, efficient, and financially savvy.”

Lily Liu

CEO, Piñata

“With Ramp, everything lives in one place. You can click into a vendor and see every transaction, invoice, and contract. That didn't exist in Zip. It's made approvals much faster because decision-makers aren't chasing down information—they have it all at their fingertips.”

Ryan Williams

Manager, Contract and Vendor Management, Advisor360°

“The ability to create flexible parameters, such as allowing bookings up to 25% above market rate, has been really good for us. Plus, having all the information within the same platform is really valuable.”

Caroline Hill

Assistant Controller, Sana Benefits