Adjusting journal entries: What they are and why they matter

- What are adjusting journal entries?

- Common types of adjusting journal entries

- How to create adjusting journal entries

- Automate adjusting entries with AI that learns your patterns and posts with precision

Adjusting entries make sure your financial statements match the reality of your operations. They update your records for income you earned but haven’t received, expenses you have incurred but haven’t paid, and other timing differences that can distort your financial picture.

If you use accrual accounting, these entries are not optional. They are essential for matching revenue and expenses to the right period, giving you a clear view of performance. Without them, your reports are incomplete. You risk making decisions based on inaccurate data, falling out of compliance, or raising red flags during an audit.

What are adjusting journal entries?

Adjusting Journal Entries

Adjusting journal entries are end-of-period updates you make to your accounting records to reflect income earned or expenses incurred that haven’t yet been captured. They ensure your financial statements accurately show your business activity for the period.

Adjusted journal entries exist because your day-to-day bookkeeping does not always align with when revenue is earned or costs are actually used. You might deliver a service this month and get paid next month. You might pay upfront for insurance that covers the next six months. Without adjusting entries, your reports would only reflect cash movement and not the financial reality behind it.

Under accrual accounting, financial statements must match income and expenses to the period they relate to, not when money enters or leaves your account. Adjusting entries makes this possible by recording these timing differences at the close of each reporting period.

This journal entry updates the general ledger so that every amount reported on the income statement and balance sheet reflects what truly occurred during the period. These updates do not involve new transactions. They revise existing account balances to make sure revenue is recognized when earned and expenses are recognized when incurred.

Common types of adjusting journal entries

Not all financial activity fits neatly into your day-to-day bookkeeping. That’s why there are different types of adjusting journal entries. You use these entries to align your financial statements with what actually occurred during the period.

The type of adjusting entry you use depends on the nature of the transaction and the accounting standards you follow. Your accountant, controller, or finance lead makes that decision based on factors like revenue timing, contract terms, and asset usage.

Accrued revenues

Accrued revenue is income you have earned but have not yet billed or collected. You record it to make sure your financial statements reflect the work you completed within the reporting period, even if the invoice goes out later.

Let’s say you finished a consulting project on March 30 but plan to invoice the client in April. That revenue still belongs in March. If you wait to record it until April, your March income will be understated, and your financials will not reflect what actually happened.

Accrued revenue is common in service-based businesses, project work, and long-term contracts. It also shows up when performance obligations are met before billing, especially in industries like SaaS, legal services, and engineering.

This entry increases your revenue on the income statement and creates an asset, usually labeled as “accrued receivables” or “unbilled revenue” on the balance sheet. You clear that asset once the invoice is sent and payment is received.

Accrued revenue adjustments help you apply the matching principle, which is a core rule under GAAP and IFRS. They also support revenue recognition standards like ASC 606 and IFRS 15, which both require revenue to be recorded when it’s earned and not when the payment arrives.

When you earn revenue but haven’t invoiced yet, it’s easy to miss that in your records. Ramp gives you real-time visibility into unbilled transactions by syncing with your systems and surfacing revenue that hasn’t been matched to payments. This helps your team catch and record earned revenue through accurate adjustments before close.

Accrued expenses

Accrued expenses are costs you've incurred during a reporting period but have not recorded yet because the bill has not arrived or payment has not been made. You recognize them through adjusting entries to make sure your financial statements reflect the full cost of doing business in that period.

If your team finishes a contractor project in June but the invoice comes in July, the expense will still be in June. Recording it in the right month prevents overstating your profits and keeps your finances aligned with the actual work performed.

Unpaid wages, interest, utilities, and professional services are common accrued expenses. These costs build up over time, even if no formal invoice is received by the period's end.

An accrued expense entry increases your expenses on the income statement and creates a liability, usually labeled as“accrued liabilities” or “accrued expenses” on the balance sheet. You remove the liability once you receive and pay the invoice.

GAAP and IFRS require you to record expenses when you incur them, not when you pay them. This helps you apply the matching principle so that expenses line up with the revenue they support.

Deferred revenues

Deferred revenue is money you've received for goods or services you haven’t delivered yet. You record it as a liability, not revenue until you complete your part of the agreement. This keeps your income statement clean and your balance sheet accurate.

If a customer pays you for a 12-month subscription in advance, you can’t recognize that full amount upfront. You recognize revenue month by month as the service is delivered. Until then, the unearned portion sits on your balance sheet as deferred revenue.

This type of adjustment is common in SaaS, insurance, and any business that gets paid before providing the full service. It’s also one of the most misunderstood areas in revenue recognition.

Deferred revenue entries reduce your reported income in the current period and shift the balance to a liability account. Over time, as you meet your performance obligations, you move the appropriate amount from the balance sheet to revenue on your income statement.

GAAP and IFRS both require this treatment under revenue recognition standards like ASC 606 and IFRS 15. These rules emphasize that revenue must reflect performance, not payment timing.

Prepaid expenses

Prepaid expenses are payments you make in advance for goods or services that benefit future periods. Until those benefits are used, the cost sits on your balance sheet as an asset. You recognize the expense gradually, based on how much of the service you have consumed.

Common examples include insurance, rent, or software subscriptions. If you pay for a 12-month policy upfront, you haven’t “spent” it all in the first month. Only a portion applies to each period. Adjusting entries move that portion from the asset account to the expense account as time passes.

This approach prevents overstating expenses in the month you made the payment. It spreads the cost in a way that matches how your business actually uses the service.

Prepaid expense adjustments help you follow the matching principle, which requires expenses to align with the period they support. Under both GAAP and IFRS, this is a core part of accrual accounting.

Without this entry, your reports may show inflated costs in one month and understated expenses in the following months. That skews your profitability and can lead to poor decisions. To reduce manual effort and avoid mistakes, 66% of accounting teams now prefer automating these recurring expenses.

Depreciation and amortization

Depreciation and amortization entries let you spread the cost of long-term assets over the periods they benefit. Instead of expensing the full amount when you purchase equipment, software, or intellectual property, you recognize a portion of the cost each period.

This approach aligns with the matching principle. It ensures that your financial statements reflect how assets lose value as they’re used, not just when you pay for them.

Depreciation applies to physical assets like machinery, vehicles, and furniture. Amortization applies to intangible assets like software licenses, patents, and trademarks. Both follow a schedule based on the asset’s useful life, and you record the adjustment consistently each period.

These entries reduce the asset’s value on your balance sheet and increase your expenses on the income statement. They do not impact cash flow but do affect profitability and tax calculations.

Accounting standards require businesses to review asset values regularly. If the asset is no longer useful or has dropped in value, you may also need to record an impairment.

For recurring adjustments like depreciation or amortization, Ramp allows you to create custom accounting rules. You can set up recurring schedules that post entries over the asset’s useful life, eliminating the need to re-enter the same data every month.

Inventory adjustments and write-downs

Inventory adjustments and write-downs help you keep your books aligned with the actual value of the goods you have on hand. These entries correct differences between what’s recorded, physically available, or still sellable.

If an inventory is lost, damaged, expired, or obsolete, it no longer holds its original value. You need to reflect that loss in your finances by adjusting the inventory balance and recording an expense. This ensures your cost of goods sold (COGS)and gross profit remain accurate.

Inventory write-downs reduce the carrying value of the stock to its net realizable value, which is the amount you expect to recover through the sale. If that value drops below the original cost, accounting rules require you to recognize the difference as a loss.

These issues are typically discovered during cycle counts or full physical inventory checks, but they can also result from demand shifts, product recalls, or supply chain delays.

These entries affect both the balance sheet and income statement. They lower inventory as an asset and increase expenses, which reduces net income.

Bad debt expense

Bad debt expense accounts for the money you are unlikely to collect from customers. When an invoice goes unpaid for too long, you record an adjusting entry to reflect the loss. This keeps your income statement accurate and realistic in your accounts receivable.

Even if you have not written off the debt yet, you still estimate the portion of receivables that will not be paid. This follows the principle of conservatism in accounting, which works around recognizing potential losses as soon as they are known.

You typically calculate bad debt using either a percentage of sales or an aging analysis of receivables. The entry reduces accounts receivable on your balance sheet and increases expenses on your income statement.

In the first quarter of 2023, the four largest U.S. banks wrote off a combined $3.4 billion in bad consumer loans, a 73% increase from the previous year. This surge underscores the importance of accurately recording bad debt expenses to reflect a company's true financial position.

Bad debt expense also supports compliance with standards like ASC 326 (Current Expected Credit Losses), which requires businesses to estimate future credit losses and not just wait until they happen.

Unearned revenue and contract liabilities

Unearned revenue and contract liabilities represent money you have collected for goods or services you haven’t delivered yet. Until you meet the performance obligation, that cash can’t be treated as revenue. You record it as a liability on your balance sheet.

If a customer pays you upfront for a 6-month service, you have not earned that revenue on day one. You move the appropriate portion from the liability account to your income statement as you deliver the service. Adjusting entries handle this shift during each reporting period.

Contract liabilities are broader. They include any obligation where you have received consideration but have not transferred control of the product or service. Under ASC 606 and IFRS 15, you are required to recognize revenue only when that control changes hands.

Failing to adjust for unearned revenue inflates your income and misstates your financial position. These entries help you report earnings that align with delivery, not just billing.

How to create adjusting journal entries

Adjusting journal entries are made at the end of each reporting period, usually monthly, quarterly, or annually. For most companies, these entries are part of the monthly close and reviewed before financials are finalized.

The actual time it takes to prepare each entry can range from a few minutes to several hours. It depends on how complex the adjustment is, how much supporting data you need, and whether you use manual or automated processes. Entries tied to depreciation or prepaid expenses are often quick. Others, like revenue recognition or contract liabilities, may take longer and require cross-team input.

- Step 1: Review your trial balance. Start by running your unadjusted trial balance. This report gives you a snapshot of all account balances before any adjustments. Focus on areas that typically require end-of-period changes, like revenue, expenses, and balance sheet accounts tied to timing differences.

- Step 2: Identify what needs adjusting. Next, identify transactions that haven't been recorded yet or are recorded in the wrong period. Look for income that’s been earned but not yet billed, expenses that have been incurred but not yet paid, or assets that need to be depreciated. Ramp helps you flag transactions that need adjustments by using AI to detect timing issues and gaps in categorization. That saves time during review and cuts down on missed entries.

- Step 3: Calculate the correct amount. Calculate how much should be recorded once you've identified what needs adjusting. Use clear documentation to support your numbers, like invoices, payroll summaries, or usage schedules. For example, if you paid an annual software fee but only used one month of it, divide the total cost over 12 months and record just that portion as an expense for the period.

- Step 4: Record the journal entry. Log in to your accounting system and enter the journal entry using standard debit and credit rules. Each adjusting entry should impact at least one balance sheet account and one income statement account. Always check that the entry balances before posting.

- Step 5: Update your trial balance. After posting your adjustments, run an updated trial balance. This report reflects all current account balances and shows you how the adjustments changed the books. Review it to make sure everything aligns. If any account looks off, go back to the source and verify the entry.

- Step 6: Document each entry. Attach support for every entry, which could be an invoice, a contract, a calculation worksheet, or a note explaining the reason for the adjustment. Keep your documentation organized and easy to find. This protects you during audits and speeds up future close cycles.

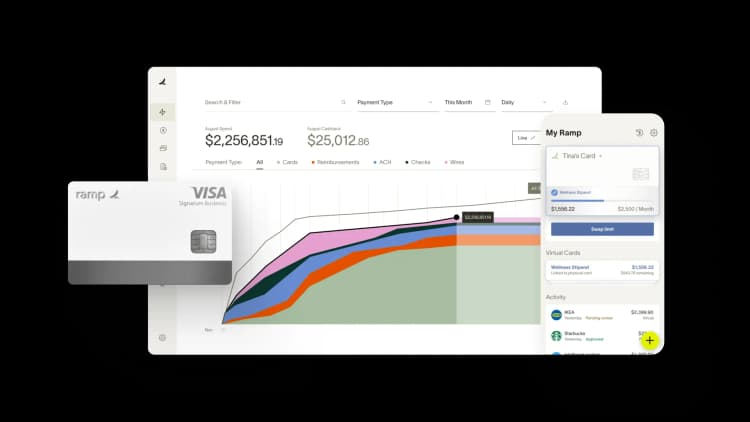

Automate adjusting entries with AI that learns your patterns and posts with precision

Adjusting entries are critical for accurate financials, but they're also time-consuming and error-prone when handled manually. You need to track prepaid expenses, accrue for unbilled costs, and ensure every transaction lands in the right period.

Ramp's accounting automation software handles adjusting entries automatically, so your books stay accurate without the manual work. The platform identifies transactions that need accruals or amortization, posts the entries to your ERP, and reverses them in the next periodbased on your accounting policies and transaction context.

Here's how Ramp automates adjusting entries:

- Auto-post accruals: Ramp detects when expenses need to be accrued (like when a receipt is missing or an invoice hasn't arrived) and posts the entry automatically so costs land in the right period

- Auto-reverse accruals: When the missing context arrives, Ramp reverses the accrual and posts the actual transaction, eliminating duplicate entries and manual cleanup

- Amortize automatically: Ramp spreads prepaid expenses and multi-period costs across the right accounting periods based on your rules, so you don't need to track and post manual journal entries every month

- Maintain full audit trails: Every automated entry includes supporting documentation, approval history, and a clear explanation of why the adjustment was made, so your books are always audit-ready

Learn more about how Ramp helps finance teams close their books 3x faster with automated adjusting entries and AI-powered accounting.

Don't miss these

“In the public sector, every hour and every dollar belongs to the taxpayer. We can't afford to waste either. Ramp ensures we don't.”

Carly Ching

Finance Specialist, City of Ketchum

“Ramp gives us one structured intake, one set of guardrails, and clean data end‑to‑end— that’s how we save 20 hours/month and buy back days at close.”

David Eckstein

CFO, Vanta

“Ramp is the only vendor that can service all of our employees across the globe in one unified system. They handle multiple currencies seamlessly, integrate with all of our accounting systems, and thanks to their customizable card and policy controls, we're compliant worldwide. ”

Brandon Zell

Chief Accounting Officer, Notion

“When our teams need something, they usually need it right away. The more time we can save doing all those tedious tasks, the more time we can dedicate to supporting our student-athletes.”

Sarah Harris

Secretary, The University of Tennessee Athletics Foundation, Inc.

“Ramp had everything we were looking for, and even things we weren't looking for. The policy aspects, that's something I never even dreamed of that a purchasing card program could handle.”

Doug Volesky

Director of Finance, City of Mount Vernon

“Switching from Brex to Ramp wasn't just a platform swap—it was a strategic upgrade that aligned with our mission to be agile, efficient, and financially savvy.”

Lily Liu

CEO, Piñata

“With Ramp, everything lives in one place. You can click into a vendor and see every transaction, invoice, and contract. That didn't exist in Zip. It's made approvals much faster because decision-makers aren't chasing down information—they have it all at their fingertips.”

Ryan Williams

Manager, Contract and Vendor Management, Advisor360°

“The ability to create flexible parameters, such as allowing bookings up to 25% above market rate, has been really good for us. Plus, having all the information within the same platform is really valuable.”

Caroline Hill

Assistant Controller, Sana Benefits