Understanding the impact of operating cash flow (OCF)

- What is operating cash flow?

- How to calculate operating cash flow: formulas + examples

- How to calculate (and interpret) your businesses operating cash flow ratio

- Operating cash flow vs free cash flow

- Operating cash flow vs net income

- How Ramp can help track and control cash flow

Most investors have been trained to look at EBITDA when evaluating the financial health of a business. Unfortunately, that number can be manipulated by inflating depreciation and amortization costs.

The operating cash flow (OCF) number is more accurate because it can provide an unencumbered view of how the company is doing after operating expenses. In this article, we’ll explain what that means and why it’s important for your business.

What is operating cash flow?

Operating cash flow is, as the name suggests, the amount of cash your business has left over after covering operating expenses. But note that we’re not talking about revenue—that’s a different number entirely. The revenue reported on the income statement is not necessarily cash-in-hand. That’s another reason why EBITDA can be misleading for investors and shareholders.

Simply put, operating cash flow is the best form of liquidity. As a business owner, it’s an important asset to have because bills and lenders must get paid and expenses need to be covered. Covering all current liabilities with operating cash flow is an indicator of a financially healthy and well-run business.

Comparing operating cash flow to net revenue at the end of a reporting period can illuminate the effectiveness of accounts receivable policies. A significant disparity, with revenue outpacing cash-on-hand, could indicate potential challenges in meeting monthly financial commitments. Since the cost of goods sold (COGS) fluctuates, maintaining adequate cash reserves is essential to cover these expenses.

As a small business owner, you recognize the importance of maintaining cash reserves to manage costs and expenses. However, growth introduces complexities that can challenge the maintenance of optimal operating cash flow (OCF). With rising costs and the potential need to extend terms to vendors and customers, it's crucial not to solely depend on EBITDA for planning. Remember, cash is a liquid asset, whereas accounts receivable is not, highlighting the importance of cash availability for operational stability.

How to calculate operating cash flow: formulas + examples

There are two ways to calculate operating cash flow. Both will get you the same result. With the indirect method, you start with the net income and then add back depreciation expense, the decrease in accounts receivable, and the increase in accrued expenses payable. Once the additions are done, deduct the increase in inventory and the decrease in accounts payable.

The direct method for calculating operating cash flow is much simpler and should be familiar to those who are using zero-based budgeting. Add up all the cash received from customers, then deduct cash paid to employees, supplier payments, and any interest payments. If you use this method, a reconciliation of net income to the cash from operating activities is required.

Most of the larger corporations in the United States use the indirect method to calculate operating cash flow because the reconciliation is built into the process. It may seem like a convoluted way of doing this, but by starting with the net income, and going through the steps of addition and subtraction, you ensure the accuracy of the result.

How to calculate (and interpret) your businesses operating cash flow ratio

The math is simple for this. Net cash flow from operations is a line item on your cash flow statement. The OCF ratio is calculated by taking that number and dividing it by your current liabilities, which can be found on your balance sheet. Your target number is 1.5-2.0. Scoring 1.0 or lower means you have a cash flow problem.

Why is this important? The operating cash flow ratio tells you whether you can pay all your current liabilities with cash and how much is left over after you do that. Companies with higher margins often have a higher OCF ratio. For instance, e-commerce cash flow ratios are typically higher than restaurant cash flow ratios because their costs are lower.

Of course, a higher margin doesn’t guarantee a higher OCF ratio. Businesses that offer net terms to their customers can create a cash flow crunch if their costs need to be covered before customer payment is received. Sellers of premium products often face this predicament. Margins are high, but they make fewer sales and need to wait to get paid.

Operating expenses on the cash flow statement include fixed costs like rent and salaries. Those don’t change when cash inflows slow down. The OCF ratio is a metric that tells the business owner when they need to seek other sources of funding, like e-commerce financing or a line of credit from the bank to cover expenses between customer payments.

Operating cash flow vs free cash flow

Operating cash flow (OCF) is the amount of cash available after all cash outflows for the reporting period have been deducted from the sum of the cash inflows. Free cash flow is the number you get when you start with operating cash flow and deduct any money spent on long-term capital expenditures (CAPEX), like property, plants, or equipment.

To avoid confusion, think of “operating” cash flow as the cash needed to “operate” your business. “Free” cash flow is what’s “free” for distribution to shareholders before you pay out any cash for debt payments, dividends, or share repurchases. Banks look at free cash flow before setting limits for loans or lines of credit. Investors use it as a liquidity metric.

Here’s an example:

Company A has $20,000 a month in cash inflows. Their cash outflows are $10,000, leaving a net cash from operations of $10,000. That’s the OCF. The OCF ratio is 1.0 because net cash = current liabilities. From there, deduct $5,000 for a new equipment purchase. Now you have $5,000. That’s your free cash number.

Operating cash flow vs net income

Operating cash flow and net income are two entirely different numbers. Net income is found on the income statement. Learn how to prepare an income statement here. It is based on revenues, not cash inflows. This is an important distinction because in accrued accounting revenue is recorded at the point of sale, not the point of payment. The cash inflow for that sale could come several months later.

Another difference is that the total net income is calculated by deducting depreciation and amortization, gain or loss on financial instruments, and interest expenses. Operating cash flow only includes cash outflows for current liabilities. The operating cash flow ratio is a tool that can be used for small business expense management.

Net income is a reported number for investors and shareholders, but it doesn’t tell the whole story. Understanding how much cash you have in hand and whether it will cover all your current liabilities is a valuable insight that can keep a company on track. That’s why OCF and the OCF ratio are critical.

How Ramp can help track and control cash flow

In the past, your accounting department would use a double-entry general ledger and T-accounts to keep track of debits and credits. Today, everything is automated. All the math is done by small business accounting software integrated with your bank. Financial reports are compiled automatically, including cash flow statements.

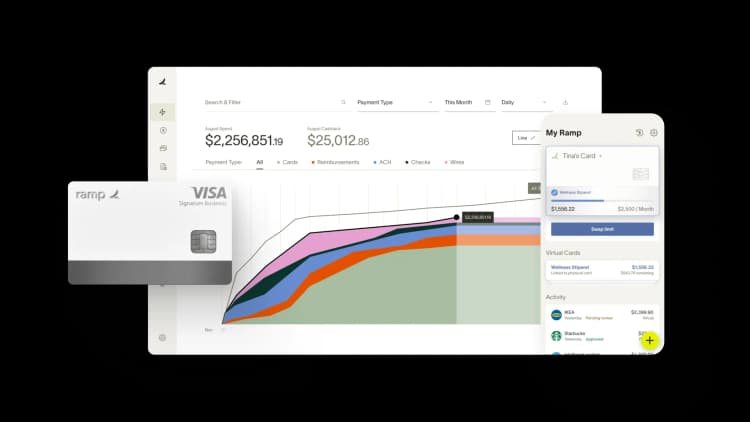

Ramp can help by connecting with your accounting automation software and giving you a dashboard where you can track expenses in real time. We can even issue you corporate charge cards so you can control where your company’s money is spent. Calculating your OCF ratio is only part of the equation. Ramp can help you improve that number and increase your liquidity.

Take our interactive demo today.

FAQs

No. EBIT is calculated by deducting the cost of goods sold (COGS) and operating expenses from revenue. Operating cash flow is calculated on the cash flow statement.

The simplest way (direct method) is to add up all the cash received from customers, then deduct cash paid to employees, supplier payments, and any interest payments.

Ramp can help by connecting with your accounting software and giving you a dashboard where you can track expenses in real time. We can even issue you corporate charge cards so you can control where your company’s money is spent.

Don't miss these

“Ramp is the only vendor that can service all of our employees across the globe in one unified system. They handle multiple currencies seamlessly, integrate with all of our accounting systems, and thanks to their customizable card and policy controls, we're compliant worldwide.” ”

Brandon Zell

Chief Accounting Officer, Notion

“When our teams need something, they usually need it right away. The more time we can save doing all those tedious tasks, the more time we can dedicate to supporting our student-athletes.”

Sarah Harris

Secretary, The University of Tennessee Athletics Foundation, Inc.

“Ramp had everything we were looking for, and even things we weren't looking for. The policy aspects, that's something I never even dreamed of that a purchasing card program could handle.”

Doug Volesky

Director of Finance, City of Mount Vernon

“Switching from Brex to Ramp wasn’t just a platform swap—it was a strategic upgrade that aligned with our mission to be agile, efficient, and financially savvy.”

Lily Liu

CEO, Piñata

“With Ramp, everything lives in one place. You can click into a vendor and see every transaction, invoice, and contract. That didn’t exist in Zip. It’s made approvals much faster because decision-makers aren’t chasing down information—they have it all at their fingertips.”

Ryan Williams

Manager, Contract and Vendor Management, Advisor360°

“The ability to create flexible parameters, such as allowing bookings up to 25% above market rate, has been really good for us. Plus, having all the information within the same platform is really valuable.”

Caroline Hill

Assistant Controller, Sana Benefits

“More vendors are allowing for discounts now, because they’re seeing the quick payment. That started with Ramp—getting everyone paid on time. We’ll get a 1-2% discount for paying early. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but when you’re dealing with hundreds of millions of dollars, it does add up.”

James Hardy

CFO, SAM Construction Group

“We’ve simplified our workflows while improving accuracy, and we are faster in closing with the help of automation. We could not have achieved this without the solutions Ramp brought to the table.”

Kaustubh Khandelwal

VP of Finance, Poshmark